1. A Travel Diary

I had left my passport at an inn we stayed at for a night or so whose name I couldn’t remember. This is how it began. The next hotel would not receive me. A beautiful hotel, in an orange grove, with a view of the sea. How casually you accepted the room that would have been ours, and, later, how merrily you stood on the balcony, pelting me with foil-wrapped chocolates. The next day you resumed the journey we would have taken together.

The concierge procured an old blanket for me. By day, I sat outside the kitchen. By night, I spread my blanket among the orange trees. Every day was the same, except for the weather.

After a time, the staff took pity on me. A busboy would bring me food from the evening meal, the odd potato or bit of lamb. Sometimes a postcard arrived. On the front, glossy landmarks and works of art. Once, a mountain covered in snow. After a month or so there was a postscript: X sends regards.

I say a month, but really I had no idea of time. The busboy disappeared. There was a new busboy, then one more, I believe. From time to time, one would join me on my blanket.

I loved those days! Each one exactly like its predecessor. There were the stone steps we climbed together and the little town where we breakfasted. Very far away, I could see the cove where we used to swim, but not hear anymore the children calling out to one another, nor hear you anymore, asking me if I would like a cold drink, which I always would.

When the postcards stopped, I read the old ones again. I saw myself standing under the balcony in that rain of foil-covered kisses, unable to believe you would abandon me, begging you, of course, though not in words—

The concierge, I realized, had been standing beside me. Do not be sad, he said. You have begun your own journey, not into the world, like your friend, but into yourself and your memories. As they fall away, perhaps you will attain that enviable emptiness into which all things flow, like the empty cup in the Daodejing—

Everything is change, he said, and everything is connected. Also everything returns, but what returns is not what went away.

We watched you walk away. Down the stone steps and into the little town. I felt something true had been spoken, and though I would have preferred to have spoken it myself, I was glad at least to have heard it.

2. The Story of the Passport

It came back but you did not come back.

It happened as follows:

One day an envelope arrived,

bearing stamps from a small European republic.

This the concierge handed me with an air of great ceremony;

I tried to open it in the same spirit.

Inside was my passport.

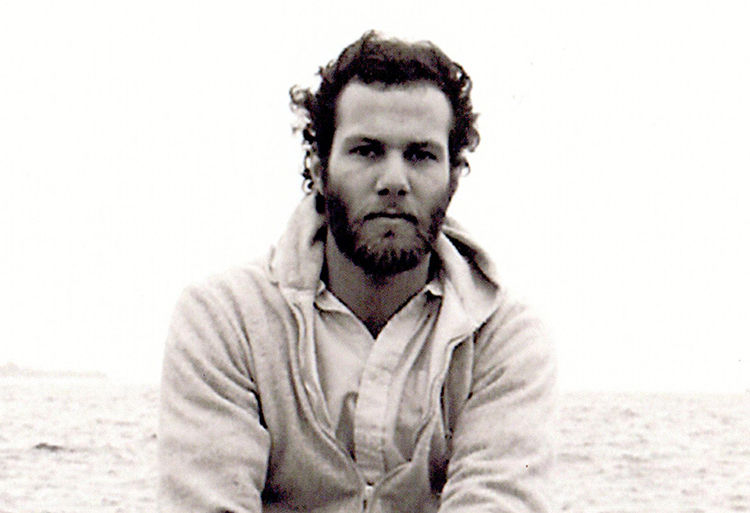

There was my face, or what had been my face

at some point, deep in the past.

But I had parted ways with it,

that face smiling with such conviction,

filled with all the memories of our travels together

and our dreams of other journeys—

I threw it into the sea.

It sank immediately.

Downward, downward, while I continued

staring into the empty water.

All this time the concierge was watching me.

Come, he said, taking my arm. And we began

to walk around the lake, as was my daily habit.

I see, he said, that you no longer

wish to resume your former life,

to move, that is, in a straight line as time

suggests we do, but rather (here he gestured toward the lake)

in a circle, which aspires to

that stillness at the heart of things,

though I prefer to think it also resembles a clock.

Here he took out of his pocket

the large watch that was always with him. I challenge you, he said,

to tell, looking at this, if it is Monday or Tuesday.

But if you look at the hand that holds it, you will realize I am not

a young man anymore, my hair is silver.

Nor will you be surprised to learn

it was once dark, as yours must have been dark,

and curly, I would say.

Through this recital, we were both

watching a group of children playing in the shallows,

each body circled by a rubber tube.

Red and blue, green and yellow,

a rainbow of children splashing in the clear lake.

I could hear the clock ticking,

presumably alluding to the passage of time

while in fact annulling it.

You must ask yourself, he said, if you deceive yourself.

By which I mean looking at the watch and not

the hand holding it. We stood awhile, staring at the lake,

each of us thinking our own thoughts.

But isn’t the life of the philosopher

exactly as you describe, I said. Going over the same course,

waiting for truth to disclose itself.

But you have stopped making things, he said, which is what

the philosopher does. Remember when you kept what you called

your travel journal? You used to read it to me,

I remember it was filled with stories of every kind,

mostly love stories and stories about loss, punctuated

with fantastic details such as wouldn’t occur to most of us,

and yet hearing them I had a sense I was listening

to my own experience but more beautifully related

than I could ever have done. I felt

you were talking to me or about me though I never left your side.

What was it called? A travel diary, I think you said,

though I often called it The Denial of Death, after Ernest Becker.

And you had an odd name for me, I remember.

Concierge, I said. Concierge is what I called you.

And before that, you, which is, I believe,

a convention in fiction.