Issue 86, Winter 1982

Julie Andrews, Walt Disney, Pamela Travers

Julie Andrews, Walt Disney, Pamela Travers

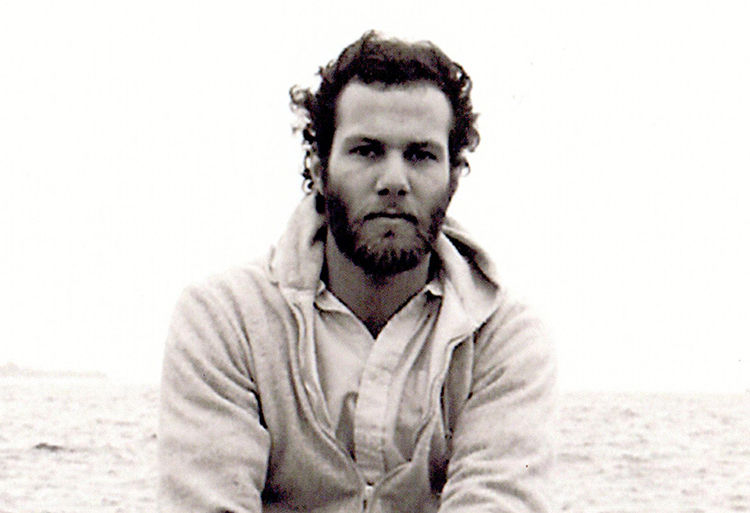

P. L. Travers’s terraced house in Chelsea has a pink door, the color of the cover of Mary Poppins in Cherry Tree Lane. In the hall is an antique rocking horse. Her study is at the top of the house: a white-walled room, crowded with books and papers, its austerity relieved by a modern rocking chair. Pamela Travers, tall and handsome, with short whitish hair, is a strong woman of great humor and charm. Once a dancer, she moves smoothly and gracefully; once an actress, she speaks with the deep clear tones of another era. Before answering a question she sometimes closes her eyes as if in meditation. There is something both mythic and modern about her. She was wearing a blue-and-white flowing dress and white pumps and silver ethnic jewelry. As she spoke, her tongue sometimes darted from the corner of her mouth, reminding one perhaps of the hamadryad in Mary Poppins—the wise snake that lectures to the transfixed Banks children. She is a master of pith and anecdote, as shown in the story she tells about paying a visit to Yeats. A young woman then, traveling by train in Ireland, it occurred to her to stop and bring a gift to the poet. She persuaded a boatman to take her to the Isle of Innisfree, where she collected great branches of rowan for her gift. A storm came up as she struggled with her branches into the train car. Finally, at Yeats’s door in Dublin, a startled maid took her in and dried her clothes by the fire. By this time, Travers, quite embarrassed, was planning an opportune escape, but as she made for the door the servant told her that Yeats was ready to see her. She ascended the stairs to meet a grandfatherly Yeats who proudly showed her an egg his canary had just laid. As they talked, Travers noticed on his desk a vase with a small slip from the colossus of branches she had brought. “That’s when I learned,” Travers concludes, “that you can say more with less.”

INTERVIEWER

That recalls your meeting with Æ [George Russell]. You must have had great courage as a young woman to call on these venerable Irishmen.

P. L. TRAVERS

I read Æ’s poems when I was a child in Australia. Later I came to England to see my relatives. But before I did that, I sent a poem to Æ, who was then editing The Irish Statesman, and with all the arrogance of youth I didn’t put any letter with it explaining myself or saying that I was Irish or anything. I just sent it with a stamped addressed envelope.

And sure enough, the stamped envelope came back. But in it was a check for two guineas and a letter that said, “I’m accepting your poem, which is a very good one, and I think it could not have been written by anyone who wasn’t Irish. If you’re ever coming to Ireland, be sure to come and see me.” Since I was going to Ireland, I did go to see him and was greatly welcomed and more poems were taken. I felt immediate mutuality with him, this great elderly man bothering about me. But he bothered about all young poets. They were always welcome.

After our visit he said to me, “On your way back through Dublin you come and see me again.” I said, “Of course, I will.” But when the time arrived and I was back in Dublin, an awful timidity came upon me. I thought he was a great man and I shouldn’t take up his time; he was doing this for politesse. And so I refrained from going to see him and went back to England. Sometime later when I opened the door, there was Æ. He said to me, “You’re a faithless girl. You promised to see me on your way back through Dublin and you didn’t.” And he added, “I meant to give you my books then and, as you weren’t there, I brought them.” And there were all his books.

INTERVIEWER

He sought you out, then?

TRAVERS

Oh, he didn’t come to London specially to see me. He had come to see his old friend George Moore. But he took me in during that time, and had time for me. I often went out to Dublin after that and saw a good deal of Æ and Yeats and James Stephens. Among the young people like myself was Frank O’Connor, who used to be called Michael O’Donovan. He was one of Æ’s protégés. There were many of them.

INTERVIEWER

Æ’s reaction to Mary Poppins is very interesting. You report his saying, “Had [Mary Poppins] lived in another age, in the old times to which she certainly belongs, she would undoubtedly have had long golden tresses, a wreath of flowers in one hand, and perhaps a spear in the other. Her eyes would have been like the sea, her nose comely, and on her feet winged sandals. But, this age being the Kali Yuga, as the Hindus call it, . . . she comes in habiliments suited to it.” It seems that Æ was suggesting that your English nanny was some twentieth-century version of the Mother Goddess Kali.

TRAVERS

Indeed, he was throwing me a clue, but I didn’t seize upon that for a long time. I’ve always been interested in the Mother Goddess. Not long ago, a young person, whom I don’t know very well, sent a message to a mutual friend that said: “I’m an addict of Mary Poppins, and I want you to ask P. L. Travers if Mary Poppins is not really the Mother Goddess.” So, I sent back a message: “Well, I’ve only recently come to see that. She is either the Mother Goddess or one of her creatures—that is, if we’re going to look for mythological or fairy-tale origins of Mary Poppins.”

I’ve spent years thinking about it because the questions I’ve been asked, very perceptive questions by readers, have led me to examine what I wrote. The book was entirely spontaneous and not invented, not thought out. I never said, “Well, I’ll write a story about Mother Goddess and call it Mary Poppins.” It didn’t happen like that. I cannot summon up inspiration; I myself am summoned.

Once, when I was in the United States, I went to see a psychologist. It was during the war when I was feeling very cut off. I thought, Well, these people in psychology always want to see the kinds of things you’ve done, so I took as many of my books as were then written. I went and met the man, and he gave me another appointment. And at the next appointment the books were handed back to me with the words: “You know, you don’t really need me. All you need to do is read your own books.”

That was so interesting to me. I began to see, thinking about it, that people who write spontaneously as I do, not with invention, never really read their own books to learn from them. And I set myself to reading them. Every now and then I found myself saying, “But this is true. How did she know?” And then I realized that she is me. Now I can say much more about Mary Poppins because what was known to me in my blood and instincts has now come up to the surface in my head.

INTERVIEWER

Has Mary Poppins changed for you over the years?

TRAVERS

Not at all, not at all.

INTERVIEWER

Has she changed for other people, do you think? Has their attitude to her altered at all?

TRAVERS

I don’t think that she must change for other people very much; I think that they would be bitterly disappointed. The other day two little boys accosted me in the street and said to me, “You are the lady who wrote Mary Poppins, aren’t you?” And I admitted it, and said, “How do you know?” And they said, “Because we sing in the choir, and the vicar told us.” So, clearly, they had thrown off their surplices and rushed after me to catch me. So I said, “Well, do you like her?” And they both nodded vigorously. I then said, “What is it you like about her?” And one of them said, “Well, she’s so ordinary and then . . .” and having said “and then” he looked around for the proper word, and couldn’t find it. And I said, “You don’t have to say any more. That ‘and then’ says everything.” And the other little boy said, “Yes, and I’m going to marry her when I grow up.” And I saw the first one clench his fists and look very belligerent. I felt there might be trouble and so I said, “Well, we’ll just have to see what she thinks about it, won’t we? And in the meantime, my house is just there—come in and have a lemonade.” So they did. With regard to your question about her altering, I do not think that people who read her would want her to be altered. And what I liked so much about that—I felt it was the highest praise—was that the boy should say, “Well, she’s so ordinary.” But that’s what she is. And it is only through the ordinary that the extraordinary can make itself perceived.

INTERVIEWER

Speaking about children’s reactions, when a little girl was asked why she liked Mary Poppins, she said, “Because she is so mad.”

TRAVERS

She is mad. Only the mad can be so sane. A young man in my house—he’s now grown up and has his own children—but when he was sixteen he said to me, “Make me a promise.” And I thought, Well, an open-ended promise is very difficult and dangerous . . . but he said, “Don’t worry, you can easily afford it.” (Of course he might have been about to ask me for a Rolls-Royce, and what would I have done then?) But I said, “Yes, very well.” So he said, “Promise me never to be clever.” “Oh,” I said, “I can easily do that, because you know I’m a perfect fool and I’m not in the least bit clever. But why do you ask that?” He said, “I’ve just been reading Mary Poppins again, and it could only have been written by a lunatic.” That goes with your girl, you see. And I knew perfectly well, because we understand each other’s language very well, that he meant “lunatic” as high praise.

INTERVIEWER

Virginia Woolf when going through a “mad” period thought she heard the birds singing in Greek. This reminds one of the babies in Mary Poppins and Mary Poppins Comes Back who understand what the Starling says. Maybe it’s the same kind of “madness”?

TRAVERS

Possibly. My starlings in Mary Poppins talk cockney, as far as I remember.

INTERVIEWER

Mary Poppins is always teaching, isn’t she?

TRAVERS

Well, yes, but I think she teaches by the way; I don’t think she sets herself up as a governess. You remember there was a governess called Miss Andrew. She’s very different from that.

INTERVIEWER

Miss Andrew’s a horror. But is Mary Poppins perhaps instructing the children in the “difficult truths” you mention in “Only Connect” as being contained in fairy tale, myth and nursery rhyme?

TRAVERS

Exactly. Well, you see, I think if she comes from anywhere that has a name, it is out of myth. And myth has been my study and joy ever since—oh, the age, I would think . . . of three. I’ve studied it all my life. No culture can satisfactorily move along its forward course without its myths, which are its teachings, its fundamental dealing with the truth of things, and the one reality that underlies everything. Yes, in that way you could say that it was teaching, but in no way deliberately doing so.

INTERVIEWER

Jane and Michael, then, learn about tears and suffering from Mary Poppins when she leaves them?

TRAVERS

She doesn’t hold back anything from them. When they beg her not to depart, she reminds them that nothing lasts forever. She’s as truthful as the nursery rhymes. Remember that all the King’s horses and all the King’s men couldn’t put Humpty-Dumpty together again. There’s such a tremendous truth in that. It goes into children in some part of them that they don’t know, and indeed perhaps we don’t know. But eventually they realize—and that’s the great truth.

INTERVIEWER

Does Mary Poppins’s teaching—if one can call it that—resemble that of Christ in his parables?

TRAVERS

My Zen master, because I’ve studied Zen for a long time, told me that every one (and all the stories weren’t written then) of the Mary Poppins stories is in essence a Zen story. And someone else, who is a bit of a Don Juan, told me that every one of the stories is a moment of tremendous sexual passion, because it begins with such tension and then it is reconciled and resolved in a way that is gloriously sensual.

INTERVIEWER

So people can read anything and everything into the stories?

TRAVERS

Indeed. A great friend of mine at the beginning of our friendship (he was himself a poet) said to me very defiantly, “I have to tell you that I loathe children’s books.” And I said to him, “Well, won’t you just read this just for my sake?” And he said grumpily, “Oh, very well, send it to me.” I did, and I got a letter back saying: “Why didn’t you tell me? Mary Poppins with her cool green core of sex has me enthralled forever.”

INTERVIEWER

And what about love? Are you implying in the Mary Poppins books that a child needs more than the love of family and friends?

TRAVERS

I have always thought that even if the child doesn’t need it, it benefits by having that extra, that plus. Every child needs to have for itself not only its loving parents and siblings and friends of its own age, but a grown-up friend. It is the fashion now to make a gap between child and grown-up, but this, I believe, has been made by the media. I was older than Jane and Michael, but I had a grown-up friend when I was about eleven. How wonderful it was to be able to have somebody other than your parents that you could talk to, who treated you as though you were a human being, with your proper place in the world. Your parents did so, too (my parents were most loving, I had a most loving childhood), but the extra friend was a tremendous plus.

INTERVIEWER

That is the kind of love that both Mary Poppins and Friend Monkey give?

TRAVERS

Yes, there is a great deal in common between Mary Poppins and Friend Monkey. Friend Monkey is really my favorite of all my books because the Hindu myth on which it is based is my favorite—the myth of the Monkey Lord who loved so much that he created chaos wherever he went.

INTERVIEWER

Almost a Christ figure?

TRAVERS

Indeed, I hadn’t dared to think of that, but yes, indeed, when you read the Ramayana you’ll come across the story of Hanuman on which I built my version of that very old myth.

I love Friend Monkey. I love the story of Hanuman. For many years, it remained in my very blood because he’s someone who loves too much and can’t help it. I don’t know where I first heard of him, but the story remained with me and I knew it would come out of me somehow or other. But I didn’t know what shape it would take.

The book hasn’t been very well received. It wasn’t given very good notices. Everybody said, “Oh, Friend Monkey. She’s writing about a monkey now. Why not more of Mary Poppins?” I wanted to do something new and, strangely enough, it wasn’t something so very new after all.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s talk about another reaction to Mary Poppins. As you know, the book was recently removed from the children’s shelves of the San Francisco libraries. The charge has been made that the book is racist and presents an unflattering view of minorities.

TRAVERS

The Irish have an expression: “Ah, my grief!” It means “the pity of things.” The objections had been made to the chapter “Bad Tuesday,” where Mary Poppins goes to the four points of the compass. She meets a mandarin in the East, an Indian in the West, an Eskimo in the North, and blacks in the South who speak in a pickaninny language. What I find strange is that, while my critics claim to have children’s best interests in mind, children themselves have never objected to the book. In fact, they love it. That was certainly the case when I was asked to speak to an affectionate crowd of children at a library in Port of Spain in Trinidad. On another occasion, when a white teacher friend of mine explained how she felt uncomfortable reading the pickaninny dialect to her young students, I asked her, “And are the black children affronted?” “Not at all,” she replied, “it appeared they loved it.” Minorities is not a word in my vocabulary. And I wonder, sometimes, how much disservice is done children by some individuals who occasionally offer, with good intentions, to serve as their spokesmen. Nonetheless, I have rewritten the offending chapter, and in the revised edition I have substituted a panda, dolphin, polar bear, and macaw. I have done so not as an apology for anything I have written. The reason is much more simple: I do not wish to see Mary Poppins tucked away in the closet. Aside from this issue, there is something else you should remember. I never wrote my books especially for children.

INTERVIEWER

You have said that before. What do you mean?

TRAVERS

When I sat down to write Mary Poppins or any of the other books, I did not know children would read them. I’m sure there must be a field of “children’s literature”—I hear about it so often—but sometimes I wonder if it isn’t a label created by publishers and booksellers who also have the impossible presumption to put on books such notes as “from five to seven” or “from nine to twelve.” How can they know when a book will appeal to such and such an age?

If you look at other so-called children’s authors, you’ll see they never wrote directly for children. Though Lewis Carroll dedicated his book to Alice, I feel it was an afterthought once the whole was already committed to paper. Beatrix Potter declared, “I write to please myself!” And I think the same can be said of Milne or Tolkien or Laura Ingalls Wilder.

I certainly had no specific child in mind when I wrote Mary Poppins. How could I? If I were writing for the Japanese child who reads it in a land without staircases, how could I have written of a nanny who slides up the banister? If I were writing for the African child who reads the book in Swahili, how could I have written of umbrellas for a child who has never seen or used one?

But I suppose if there is something in my books that appeals to children, it is the result of my not having to go back to my childhood; I can, as it were, turn aside and consult it (James Joyce once wrote, “My childhood bends beside me”). If we’re completely honest, not sentimental or nostalgic, we have no idea where childhood ends and maturity begins. It is one unending thread, not a life chopped up into sections out of touch with one another.

Once, when Maurice Sendak was being interviewed on television a little after the success of Where the Wild Things Are, he was asked the usual questions: Do you have children? Do you like children? After a pause, he said with simple dignity: “I was a child.” That says it all.

But don’t let me leave you with the impression that I am ungrateful to children. They have stolen much of the world’s treasure and magic in the literature they have appropriated for themselves. Think, for example, of the myths or Grimm’s fairy tales—none of which were written especially for them—this ancestral literature handed down by the folk. And so despite publishers’ labels and my own protestations about not writing especially for them, I am grateful that children have included my books in their treasure trove.

INTERVIEWER

Don’t you have a new Mary Poppins book coming out?

TRAVERS

You know, for the longest time I thought I was done with Mary Poppins. Then I found out she was not done with me. My English publisher, William Collins, will release Mary Poppins in Cherry Tree Lane. It will be out in the U.S. in the fall of 1982 with Delacorte/Dell. After all those years, Mary Poppins showed me new dimensions of herself and other characters. I will be interested to learn how you and other readers find it. Then in the fall my English publisher will reissue Friend Monkey.

INTERVIEWER

Could you write a Mary Poppins book to order?

TRAVERS

No, never. As I have said, I am summoned. I do not wait around, though; I write on other things. For example, I am a regular contributor to the periodical Parabola: Myth and the Quest for Meaning, my latest piece being “Leda’s Lament.” Anyway, everything comes out of living with an idea. If I knew how to summon up inspiration, would I give my secret away?

INTERVIEWER

Even if you might be termed an “inspired” or mystical writer, do you have to set yourself a daily schedule of writing?

TRAVERS

In a way I’m never not doing it. When I’m going to buy, let us say, a tube of toothpaste, I have it in me. The story or lecture or article is moving. And I make a point of writing, if only a little, every day, as a kind of discipline so that it is not a whim but a piece of work.

INTERVIEWER

Do you read much before or during writing?

TRAVERS

No. I read myths and fairy tales and books about them a great deal now, but I very seldom read novels. I find modern novels bore me. I can read Tolstoy and the Russians, but mostly I read comparative mythology and comparative religion. I need matter to carry with me.

INTERVIEWER

Do you compose in longhand or at the typewriter?

TRAVERS

I do a little bit of both. It’s very strange. My handwriting, when I’m writing on paper before I put it onto the typewriter, is quite different—it’s somebody else’s handwriting. I’m always surprised to see it. Perhaps I’m not writing at all; perhaps there is somebody else doing it. I so often wonder: Do these ideas come into the mind or are they just instinctive or are they . . . ?

INTERVIEWER

“Throngs of living souls,” as Æ suggests.

TRAVERS

I just don’t know. I don’t think I’m a very mental person. When I write it’s more a process of listening. I don’t pretend that there is some spirit standing beside me that tells me things. More and more I’ve become convinced that the great treasure to possess is the unknown. I’m going to write, I hope, a lot about that. It’s with my unknowing that I come to the myths. If I came to them knowing, I would have nothing to learn. But I bring my unknowing, which is a tangible thing, a clear space, something that’s been made room for out of the muddle of ordinary psychic stuff, an empty space.

INTERVIEWER

In one of your essays you recall the Zen statement “Not created but summoned” when speaking about this.

TRAVERS

Yes, that really describes it. You know C. S. Lewis, whom I greatly admire, said there’s no such thing as creative writing. I’ve always agreed with that and always refuse to teach it when given the opportunity. He said there is, in fact, only one Creator and we mix. That’s our function, to mix the elements He has given us. See how wonderfully anonymous that leaves us? You can’t say, “I did this; this gross matrix of flesh and blood and sinews and nerves did this.” What nonsense! I’m given these things to make a pattern out of. Something gave it to me.

I’ve always loved the idea of the craftsman, the anonymous man. For instance, I’ve always wanted my books to be called the work of Anon, because Anon is my favorite literary character. If you look through an anthology of poems that go from the far past into the present time, you’ll see that all the poems signed “Anon” have a very specific flavor that is one flavor all the way through the centuries. I think, perhaps arrogantly, of myself as “Anon.” I would like to think that Mary Poppins and the other books could be called back to make that change. But I suppose it’s too late for that.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think of the books of Carlos Castaneda?

TRAVERS

I like them very much. They take me into a world where I fear I will not belong. It’s a bit more occult than my world, but I like Don Juan’s idea about what a warrior is and how a warrior should live. In a way, we all have to live like warriors; that’s the same as being the hero of one’s own story. I feel that Castaneda has been taken into other dimensions of thinking and experiencing. I don’t pretend to understand them, and I think I understand why Castaneda is so slow to give interviews and tries to separate himself from all of that. He doesn’t want to explain. These things can’t be explained in ordinary terms.

You know, in America, everybody thinks there’s an answer to every question. They’re always saying, “But why and how?” They always think there is a solution. There is a great fortitude in that and a great sense of optimism. In Europe, we are so old that we know there are certain things to which there is not an answer. And you will remember, in this regard, that Mary Poppins’s chief characteristic, apart from her tremendous vanity, is that she never explains. I often wonder why people write and ask me to explain this and that. I’ll write back and say that Mary Poppins didn’t explain, so neither can I nor neither will I. So many people ask me, “Where does she go?” Well, I say, if the book hasn’t said that, then it’s up to you to find out. I’m not going to write footnotes to Mary Poppins. That would be absolutely presumptuous, and at the same time it would be assuming that I know. It’s the fact that she’s unknown that’s so intriguing to readers.

INTERVIEWER

There’s that same quality about Castaneda.

TRAVERS

There is. His is a more deliberate unknown. It’s as though he were hiding, I often think. And I don’t know why, psychologically, he is doing that but I respect that hiding nonetheless. He has some idea in it.

You see, you’ve got a great wealth of myth in America and he has tapped it. And some of the writers on American Indian affairs have tapped it. But in a way it’s foreign to us. You see how often Castaneda, as a modern man and non-Indian, becomes sick, physically sick, with the experiences. It almost seems to be that they’re not for us. The Mexican Indians are, after all, a very old race.

I lived with the Indians, or rather I lived on the reservations, for two summers during the war. John Collier, who was then the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, was a great friend of mine and he saw that I was very homesick for England but couldn’t go back over those mined waters. And he said, “I’ll tell you what I’ll do for you. I’ll send you to live with the Indians.” “That’s mockery,” I replied. “What good will that do me?” He said, “You’ll see.”

I’d never been out West and I went to stay on the Navajo reservation at Administration House, which is at Window Rock beyond Gallup. Collier had sent a letter to the members of the committee at Administration House and asked them to take me about so that I could see the land and meet the Indians. They very kindly did. Fortunately, I was able to ride and I was equipped with jeans and boots and a western saddle. Then I saw that the Indian women wore big, wide, flounced Spanish skirts with little velvet jackets. And I, who don’t like trousers very much, said I must have one of those. So they made me a flounced skirt and a velvet jacket, and I rode with the Indians. It was wonderful the way they turned towards me when, instead of being an Eastern dude, I put on their skirt.

One day the head of Administration House asked me if I would give a talk to the Indians. And I said, “How could I talk to them, these ancient people? It is they who could tell me things.” He said, “Try.” So they came into what I suppose was a clubhouse, a big place with a stage, and I stood on the stage and the place was full of Indians. I told them about England, because she was at war then, and all that was happening. I said that for me England was the place “Where the Sun Rises” because, you see, England is east of where I was. I said, “Over large water.” And I told them about the children who were being evacuated from the cities and some of the experiences of the children. I put it as mythologically as I could, just very simple sayings.

At the end there was dead silence. I turned to the man who had introduced me and said, “I’m sorry. I failed, I haven’t got across.” And he said, “You wait. You don’t know them as well as I do.” And every Indian in that big hall came up and took me silently by the hand, one after another. That was their way of expressing feeling with me.

I never knew such depths of silence, internally and externally, as I experienced in the Navajo desert. One night I was taken at full moon away into the desert where they were having a meeting before they had their dancing. There were crowds of Indians there, about two thousand under the moon. And before the proceedings began there was no sound in the desert amongst those people except the occasional cry of a baby or the rattle of a horse’s harness or the crackling of fire under a pot—those natural sounds that really don’t take anything from the silence.

They waited it seemed to me hours before the first man got up to speak. Naturally, I didn’t understand what they were saying. But I listened to the speeches and I enjoyed the silences all night long. And when the night was far spent, they began to dance. Not in the usual dances of the corn dance; they had their ordinary clothes on and were dancing two-and-two, going around and around a fire, a man and a woman. And I was told that if you’re asked to dance by a man and you don’t want to dance, you give him a silver coin. So one Indian did come up, but I went with him. I couldn’t do the dance, even though it wasn’t a very intricate dance; it was more a little short step round and round, just these two people together. So we two strangers danced around the fire. It was very moving to me. And we came back to the House in the early morning.

And, of course, I saw lots of the regular dances with Navajos and the Hopis, and later with the Pueblos. The Indians in the Pueblo tribe gave me an Indian name and they said I must never reveal it. Every Indian has a secret name as well as his public name. This moved me very much because I have a strong feeling about names, that names are a part of a person, a very private thing to each one. I’m always amazed at the way Christian names are seized upon in America as if by right instead of as something to be given. One of the fairy tales, “Rumpelstiltskin,” deals with the extraordinary privacy and inward nature of the name. It’s always been a big taboo in the fairy tales and in myth that you do not name a person. Many primitive people do not like you to speak and praise a child to its face, for instance, and they will make a cross or sign against evil when you do that, even in Ireland sometimes.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think of the contemporary interest in religion and myth, particularly among young people? Do you sense that in the last few years a large number of people have grown interested in spiritual disciplines—yoga, Zen, meditation, and the like?

TRAVERS

Yes, definitely. It shows the deep, disturbed undercurrents that there are in man, that he is really looking for something that is more than a thing. This is a civilization devoted to things. What they’re looking for is something that they cannot possess but serve, something higher than themselves.

I’m all with them in their search because it is my search, too. But I’ve searched for it all my life. And when I’m asked to speak about myth, I nearly always find it’s not known. There’s no preparation. There’s nothing for the words to fall on. People haven’t read the fairy tales.

INTERVIEWER

What reading would you recommend for children and adults?

TRAVERS

I should send people right back to the fairy tales. The Bible, of course. Even the nursery rhymes. You can find things there. As I was saying, when you think of “Humpty-Dumpty”—“. . . All the King’s horses and all the King’s men couldn’t put Humpty together again”—that’s a wonderful story, a fable that some things are impossible. And when children learn that, they accept that there are certain things that can’t be, and it’s a most delicate and indirect way to have it go into them.

I feel that the indirect teaching is what is needed. All school teaching is a direct giving of information. But everything I do is by hint and suggestion. That’s what I think gets into the inner ear.

INTERVIEWER

Nowadays, then, you see behind the headlines a renewed interest in the Divine Mother.

TRAVERS

I’ve said several times that I think women’s liberation is, in a way, an aspect of realizing the Divine Mother. Not that I think women’s libbers are Divine Mothers. Far from it. But I think the feminine principle, which we could say the Divine Mother embodies, is rising. All I want is that they don’t use the feminine principle in order to turn themselves into men. We have all that we need as women. We just don’t recognize it, some of us.

I am happily a woman. Nothing in me resents it. All of me accepts it and always has. Mind you, I haven’t suffered. I haven’t been in a profession where women are paid less than men. Nothing has been hard for me as a woman. But I sympathize with women who want to live themselves to the full. But I don’t think you can do that by being a Madison Avenue executive or president of a women’s bank. All those things I’ve never wanted.

Women belong in myth. We have to think of the ideas of yin and yang. So I feel we’re really sitting, if we only knew, exactly where we ought to be, where the Divine Mother sits. If we don’t know this is so, then it isn’t so.

INTERVIEWER

If Mary Poppins invented you, not vice versa, as you say, can you imagine what would have happened to you if she hadn’t come along?

TRAVERS

Oh, I’ve never thought about it. It has never occurred to me to think that way, because, you see, we aren’t given the opportunity of leading parallel lives. What would I have done if I hadn’t done this? I have no means of knowing, because one life is all we get. It would have had something to do with the stage, dancing. But then, actresses grow old, dancers grow wobbly, whereas a writer still has a typewriter. And I think I’ve been learning and growing in writing all these years. If there’s a life after death, I want to work.

INTERVIEWER

Is there going to be another Mary Poppins book?

TRAVERS

Well, I have a sense of another lurking—“lurking” is the word, like a burglar, round and round the house. That’s all I can say at the moment.