Issue 242, Winter 2022

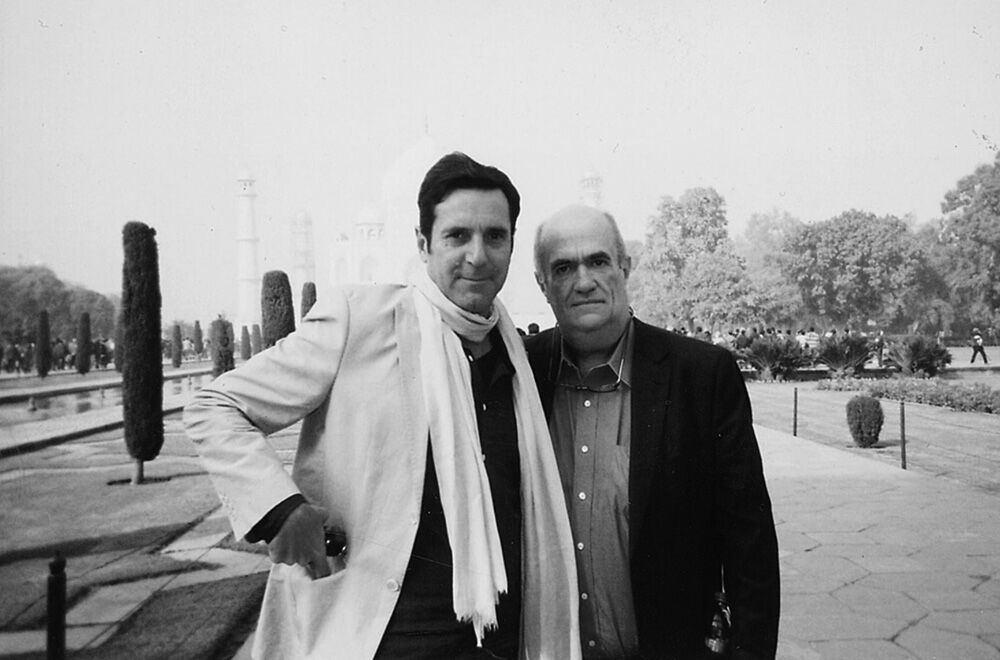

With his partner, Hedi El Kholti, at the Taj Mahal, 2016. Courtesy of Colm Tóibín.

Often, during the course of my interview sessions with Colm Tóibín, which numbered more than a dozen and took place across time zones—he was in Los Angeles, in the Catalan Pyrenees, on the Ballyconnigar coast of his native County Wexford—a disposable fountain pen would dart into view, held in his hand and used to emphasize a point about process or method or about the novel he had been working on before our conversation began and to which, after it had ended, he would return. Tóibín’s friends know that these pens are part of the deal. See Tóibín, see a Pilot V, or more than one—tucked into a jacket pocket, waiting on a desk, scattered like cigarette butts across the kitchen countertop at one of the parties for which his Georgian town house has been legendary in Dublin.

The novel in progress, a sequel to Brooklyn (2009), will be his eleventh. He is also the author of two books of short stories and several collections of essays and literary journalism. A book of poetry, Vinegar Hill, came out this past spring. Even before his debut novel, The South, appeared in 1990, he had published four works of nonfiction—a book about Barcelona, an account of walking the Irish border during one of the most turbulent periods of the Troubles, and a pamphlet on writing and public life and another about the trial of the Argentinian generals. There have been two plays and a screenplay, and the libretto for an opera, The Master, which is based on his 2004 novel about Henry James and was performed in Wexford this past fall.

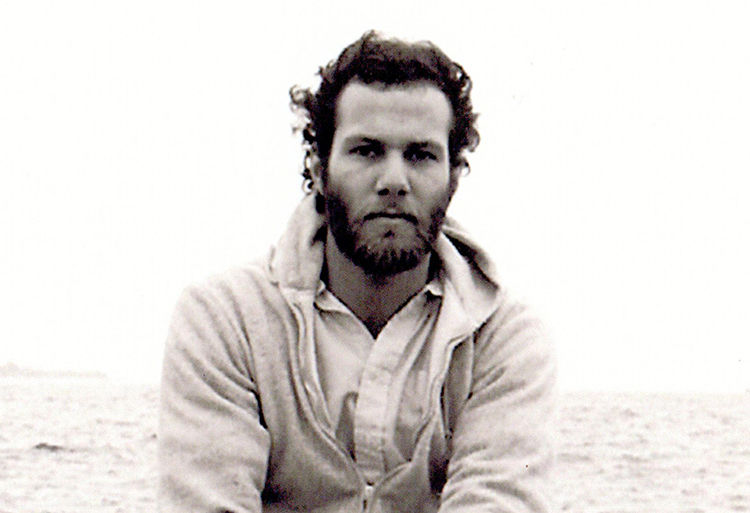

Tóibín talks about writing as work. He says, “I was working very hard,” or “I was just working,” or, when describing a breakthrough with a character or in his sense of how to frame a narrative, “I could work with that,” or, even more forcefully and with a palpable sense of relief, “Then I knew I could work.” One gets the feeling that, for Tóibín, any non-Work, whether it be teaching or traveling or just attending a dinner party—people are constantly holding dinner parties in his honor—becomes a kind of debt that must be repaid back at the desk, on a daily basis and especially at the crunch point of each narrative, when there is the opportunity to face and banish whatever technical problem has been obstructing him from Work. He overcomes it—makes a decision about form or backstory or perspective—and then he is again in the glorious fullness of the work, and he writes and writes in his notebooks with those Pilot V pens, until he can stop. Sometimes, as a break, he will bid on a painting, which he did during our first conversation. Tóibín has more art than he has walls. He was born in Enniscorthy, County Wexford, in 1955, and these days he splits his time between LA, where he lives with his partner, the writer and Semiotext(e) editor Hedi El Kholti, and New York City, where he teaches at Columbia University. But there are pens on both sides of the Atlantic, and high up in the Pyrenees.

INTERVIEWER

What is your view on period drama?

COLM TÓIBÍN

A few years ago, every Sunday night I would visit a friend who was an old lady, Beatrice von Rezzori. I would walk across the park to her house in Manhattan, and we’d order Chinese food and sit together with little trays on our laps, fully content. We would watch what I called Downtown Abbey. When that ended, we watched Victoria. It was all oddly relaxing and it was, at the same time, simply preposterous.

I have no interest in the Victoria & Albert school of novel writing—descriptions of the upholstery in the cab and what the prime minister’s waistcoat is like. When I am writing a novel, I have no responsibility to the subject, only to the reader. In writing about Henry James, it was clear that my job was to keep the drama psychological—about his demons, what was haunting him. Obviously there are always temptations. There’s a moment in 1896 when James gets his Kensington apartment wired for electricity for the first time—if you’re a certain sort of novelist, set pieces like that are gold. I could have gone on for pages about where the plugs were, the kind of light, how the evenings were changed by electricity. I wanted to write it, but I realized that, if I got it right, people might respond, “It’s marvelous the way you capture the period.” I hate the period. I hate people capturing the period.

INTERVIEWER

But don’t you do a lot of research, like a biographer might?

TÓIBÍN

I read everything, of course. With The Magician (2021), I started really paying attention to books about Thomas Mann after I reviewed three biographies that came out in the same week in 1996. I knew by 2005, when I went to LA for the first time, that I wanted to see inside his house there, inside his study. I knew that if I could be in that room, I could get the sound or some sense of the book.

Later, I became interested in how Mann got to writing Doctor Faustus, the way he used Schoenberg as a model without understanding Schoenberg’s music. To come to terms with the music, he had to consult Adorno, and Schoenberg couldn’t bear Adorno. I was fascinated by these relationships and by the fact that Mann took pages of Adorno’s work and put them directly into Faustus without crediting him. To make sense of it all, I even had someone come and teach me the twelve-tone technique. The problem was that I was becoming involved in a sort of fictional game about classical music and all these famous figures. My two editors, Mary Mount in London and Nan Graham in New York, felt that whatever Adorno represented was taking away from what was actually emerging—without my having planned it—which was a family story about a man whose son commits suicide. If I didn’t recognize that, I was going to lose the book. So I had to do a lot of cutting.

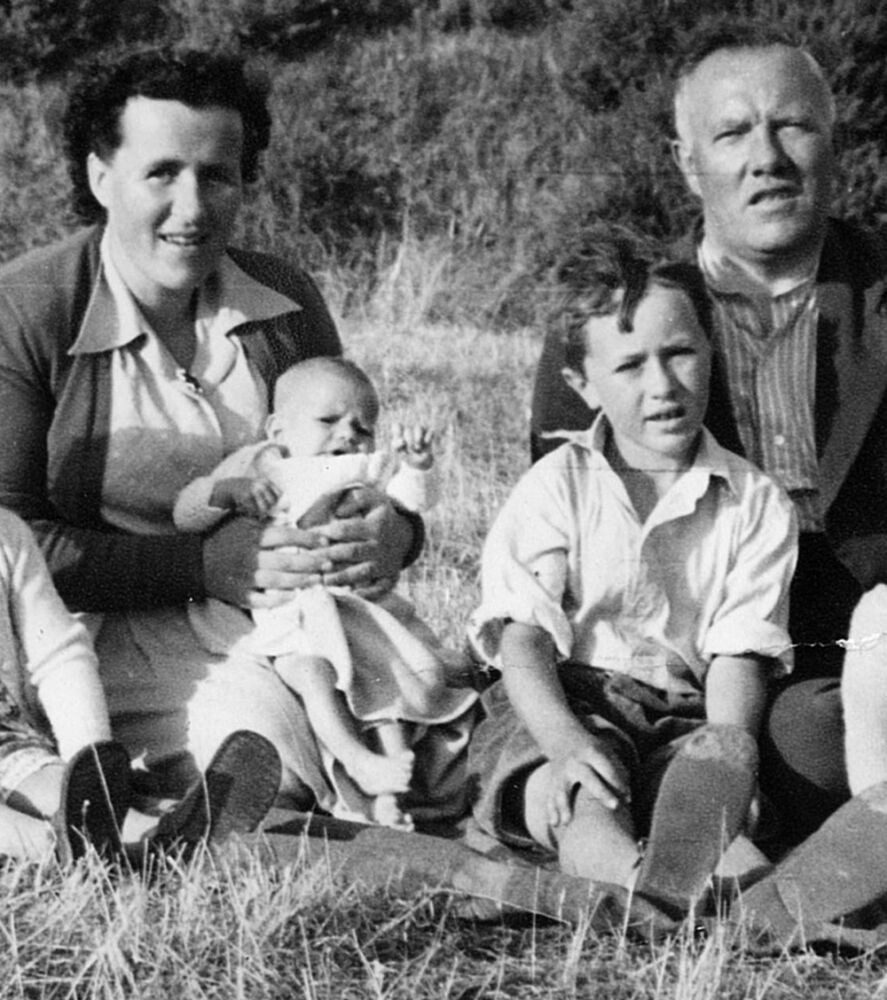

Tóibín, at left, with his parents and older brother, Ballyconnigar, County Wexford, Ireland, 1955. Courtesy of Colm Tóibín.

INTERVIEWER

How much are we talking?

TÓIBÍN

Fifty-five thousand words, most of them at the suggestion of Mary. As soon as I had her response, it was a great liberation. These words had to go! Nobody cares about some row between a composer and a novelist in 1948. Or so I began to think. It’s always tempting to show off, to show how much you know. The thing about writing novels is that it must be a form of self-suppression. You don’t matter. The page is not a mirror. In the world of Irish traditional singing, people will sometimes say of a performer, “Yeah, he was great, but I heard the singer—I didn’t hear the song.” That’s considered a withering critique. If you’re the singer, you have to bury yourself in the song.

INTERVIEWER

Do you enjoy being edited?

TÓIBÍN

With novels like The Heather Blazing (1992), The Blackwater Lightship (1999), Brooklyn, and Nora Webster (2014), there was very little editing. Being edited is a sort of shaming process—there are times when you look at a proposed edit and think, I really should have seen that. Nan, for example, went through each paragraph of The Master to show me how, not infrequently, the last sentence of the paragraph wasn’t needed. Deborah Treisman at The New Yorker has done a very good job at keeping my stories under seven thousand words. I’ve been working with Peter Straus since 1990, first as my editor and then as my agent, and when I sent him The Blackwater Lightship, he said, “Great. Would love to see when the ending comes.” I said, “That is the ending”—I thought what I had was tremendous. He told me to see what I could do. I would fax a new attempt to him in the evening and he would have it read by the morning, and he would say either “Go back to where you were” or “This is maybe something …” It went on for quite some time. Peter is an essential element. Also, I just like talking to him.

INTERVIEWER

Do you show anyone else your work in progress?

TÓIBÍN

I have two friends in Dublin whom I will show something to as soon as I write it. I’m not looking for a vast critique, just some recognition—you know, Look who’s the best boy! I’ve been working!

INTERVIEWER

Do you write on the computer?

TÓIBÍN

I’ve been writing by hand since The Blackwater Lightship—I was in Barcelona, and I suddenly had a chapter in my head, and no machine with me. I realized that I liked making the letters with my pen, and so this became a tactile pleasure that made me look forward to going back to the book. Now I leave the left-hand page of my notebook blank so I can rewrite a paragraph without having to find space for it somewhere.

The point, with the first draft, is to really concentrate, to work as though you won’t get another chance. That’s vital because you can’t, oddly enough, add significant rhythm to material on a second draft. With some scenes especially, you can change words, but the momentum has to be right to begin with.

Before I work, I tend to know what I am setting out to do. It’s almost embarrassing the amount of preparation, for example, I put into writing the scene in Nora Webster where she thinks she’s seen her late husband, Maurice. I knew it could only be written in one go—I had to get every moment of it down as though it were happening in real time. It was a question of controlling the emotion sufficiently, like an athlete would with breath.

INTERVIEWER

What kind of preparation did you do?

TÓIBÍN

I spent a few days on my own in Wexford, in a place I associate with my parents, building up to it, putting on the Archduke Trio. I had to have the exact recording that Nora did. I was rereading various works in which ghosts appear—Hamlet, “Little Gidding,” the scene in The Magic Mountain with the Ouija board, Milton’s sonnet about seeing his dead wife—and preparing myself almost physically for it. On the day I wrote it I got up at probably six or seven and put on the music, and got myself into a sort of condition. I kept bringing it back to this one part of the Archduke Trio. Then I turned the music off and I wrote it.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a writing routine?

TÓIBÍN

My job is to finish the book. If that involves twelve- or fifteen-hour days, then so be it. The difficult thing is that halfway through writing a novel, you already know the whole story. I think that’s why a lot of people give up around then—you’ve had all the realizations. Poetry is different. The connection between the emotion and the rhythm hits you in the strangest moments—and then you’ve got to go with it. Pick the wrong time to write a poem, and you will overdo it or underdo it.

INTERVIEWER

Didn’t you start out as a poet?

TÓIBÍN

When I was twelve, I started writing poems every day, every evening. Not only that but I followed poetry as somebody else of that age might follow sport. I read the book reviews in the Irish Times incredibly carefully. I was looking for books by the names in the paper—Eavan Boland, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Thomas Kinsella—and going up to Dublin for the day, bringing home Ariel and Death of a Naturalist. I began to send my writing to a magazine for young people, run by a very nice Capuchin priest, and they published my work. They wrote me very interesting letters—I remember they wanted everything shortened.

INTERVIEWER

Was poetry important in your family?

TÓIBÍN

My father had a younger brother, Philip, who died of tuberculosis in 1940, and who had written poetry in Irish. People said no one could hold a candle to Phil. And in the early forties my parents worked on a local literary magazine, and my mother had poems published in it. She was a great reader and she would move around the kitchen thinking that she was Othello. I remember I was on a train once going somewhere out of London with Sebastian Barry, and lines that my mother constantly recited just came into my head. I said to Sebastian, who had his laptop: “Can you Google something for me now?” He said, “Okay.” And I quoted: “That must be why the big things pass / And the little things remain / Like the smell of the wattle by Lichtenberg / Riding in, in the rain.”

“Is that anything?” I asked him. And he found it. It’s by Kipling. We laughed. Kipling!

“Sweetheart, do not love too long: / I loved long and long, / And grew to be out of fashion / Like an old song.” That would be a constant part of the day with my mother. “Who steals my purse steals trash.” The quoting would just go on and on.

INTERVIEWER

Were you a precocious child?

TÓIBÍN

The strange thing is, until I was eight or nine, I couldn’t read a book. I couldn’t do it and I didn’t do it. I couldn’t even read the comics—The Hotspur, Judy. I wasn’t dyslexic or anything like that. It simply became clear that I wasn’t any good at school, and that was odd, because no one in our family was no good. My older brother, Brendan, was really brilliant as a sportsman, and he spent his life going out with a hurling stick in his hand. Both of my sisters were diligent and clever and did incredibly well.

In those years, everyone was so interested in “getting on”—meaning finding a good job, becoming a civil servant. My parents knew all the ways of getting into a state job or a semi–state job—knew exactly what was needed—and my father, who was a teacher, was always introducing students to ideas of what they could work at, because in those days work was very scarce. So, they were—puzzled about me—there was a joke that if I didn’t learn to read, then I could get a job in Enniscorthy as a draper’s assistant. It became awkward because my brother Niall, who was younger than me, was immensely bright. He began to read before I did, and that became a matter of some comment.

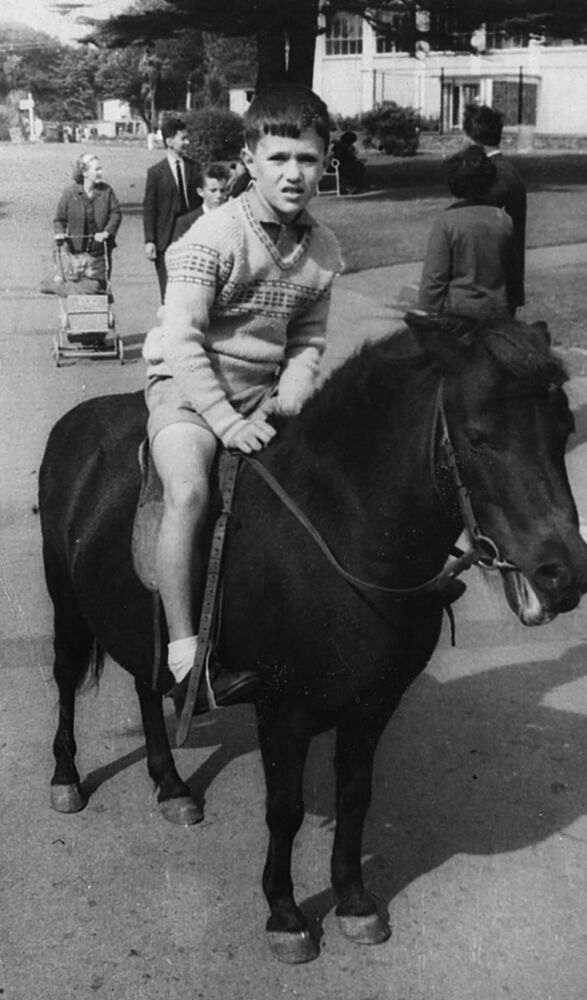

At the Dublin Zoo, ca. 1965. Courtesy of Colm Tóibín.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think you were in some way in hiding, in those years?

TÓIBÍN

I don’t know about that, because what happened afterward was so traumatic—this period didn’t feel like that.

INTERVIEWER

You’re talking about the death of your father, when you were twelve.

TÓIBÍN

The problems at home began earlier. My father was one of those men who wouldn’t go to the doctor. In 1963—when I was eight and Niall was four—he finally went, and was driven straight to a hospital in Dublin. He had a massive brain operation there, and was in hospital for a very, very long time. My mother chose—and it was her decision—to stay with him, and she stayed for three months, perhaps more. My brothers, my sisters, and I remained at home. At first it was fine, because there was an aunt who would come and look in on us. But then it was determined that Niall and I were too young for this, and we were moved in with another aunt, who lived in County Kildare. We didn’t go to school, and we didn’t see our mother, during all this time. And it affected our lives.

When my father came home he had a huge gash on his forehead, and he had more or less lost his speech. He must have had a stroke, because he had trouble with his mobility as well. No one had warned us. He would try to talk, and I couldn’t understand what he was saying. That’s when my stutter began. The worst thing was that my father decided to go back to teaching, and there was nobody to stop him—and my older brother was in his class. My father lived for four more years.

INTERVIEWER

Had you and your father been very close?

TÓIBÍN

We got on perfectly and went around together. There was no moment in the company of him and his friends when I felt I was a nuisance. Around 1960, he bought the Enniscorthy Castle for the town as a museum. He and a local priest had run dances to raise the money. I was always at the castle with him, or waiting for him to come home from the castle. My father was also involved in a very serious way with the Fianna Fáil Party, the ruling political party in Ireland, and with various charities that had to do with the Catholic Church. I vividly remember the 1965 election, for which I was licking envelopes, the whole house filled with election fever. He had all these conversations in the castle with local organizers, these men smoking and telling stories and a woman who’d taken part in the 1916 Rebellion. There was nothing in it that was of the slightest interest to me—it was merely that I got into the habit of being with my father, and that became what I wanted to do. I would come over from the primary school at the end of my day and slip in to the back of his classroom at the secondary school and wait till he was ready.

This ended in May of 1967. There was a Fleadh Cheoil, a big traditional music festival, in Enniscorthy, and my father was off at the castle, which was packed. Children were forbidden from going downtown because there were hippies and people smoking drugs, but I told my mother that my father had asked me to go. Once I got there, he couldn’t get rid of me, so we went to a pub together, and it stayed open very late. There were all sorts of strange people and someone singing “Her eyes, they shone like diamonds.” My father had a stroke that night, and then he died in July. In September, my sisters left home to go to school and university, and my older brother had also left, so it was just myself, my younger brother, and my mother for the first time—and I started at the secondary school where my father had been a teacher. He became unmentionable. No one in that school ever said anything about him. And no one at home much either.

INTERVIEWER

What do you remember of your mother’s grief?

TÓIBÍN

It was very open at first, and then it wasn’t. The big problem was that the teachers’ union had not negotiated a proper widow’s pension, so we lost the car and she had to return to the office where she worked before she was married. She had loved her days at home, and I think she couldn’t quite believe she was back to work. Every morning she took a particular route across town that was sort of awkward, using side streets, as though there was a shame attached to her. She didn’t want to run into anybody she knew, because they would stop her to sympathize once more and that would make her cry. The entire business of being part of a married couple in those years meant that if your husband died, you were so open to being patronized and generally annoyed by everyone. My mother would buy a sheepskin coat and on her way to Mass someone would stop her and say, Oh!—wondering how she’d gotten the money for it.

INTERVIEWER

Was it a relief to leave Enniscorthy for University College Dublin?

TÓIBÍN

Yes, I was starting over. It was very exotic. There was no downside. In those first two months it was Denis Donoghue on the modern novel, and Seamus Deane on practical criticism and how to read a poem. There was a general atmosphere of people writing poetry and sending it out and getting to know older poets. Seamus Heaney was living in Wicklow, and he would come to anything the students asked him to for no fee. Thomas Kinsella was the same. I was at the first reading of Heaney’s North, in 1975. When Derek Mahon’s The Snow Party came out, my friend the poet Gerard Fanning got an early copy and we went through it poem by poem one night. I was watching particularly what Gerard, a few years older than me, was doing—looking at his drafts and seeing how a poem would come to him. Even at eighteen he and Aidan Mathews were writing very well, and getting published, sometimes in serious journals. There was a UCD magazine called St. Stephen’s, and I published a poem in that. But the thing was that my work was no good. I wasn’t revising enough, but that didn’t stop me from really wanting to publish.

INTERVIEWER

You studied English and history. Were you equally engaged in your history classes?

TÓIBÍN

I enjoyed every moment of them. What was interesting was that in the department there was an old Fine Gael system of thinking—Fine Gael being the other political party at that time—which eliminated anything to do with Irish nationalism from the agenda, meaning that there was no instance in those years when the famine was mentioned—nor, indeed, the Fenians. The F-words. It was all about parliamentary history and Daniel O’Connell and Charles Stewart Parnell and, in the twentieth century, Éamon de Valera. You were removed from whatever context you might have come from, such as mine.

INTERVIEWER

Did the Troubles push in on conversations in the department?

TÓIBÍN

Yes, they did. And in 1973, I got a summer job working in the National Archives, cataloging the 1911 census. There was a guy there called Martin Lacey, who had made the journey, as many people had, from radical socialist republicanism to a radical socialist sort of two-nations anti-republicanism. This meant that he was implacably opposed to the IRA campaign of violence in Northern Ireland. By the time I came back to UCD in September, I was also anti-republican, and quite radically so. I was a supporter not only of Conor Cruise O’Brien’s position—he was fiercely opposed to the ideology of the IRA—but of an organization called BICO, the British and Irish Communist Organization. I was not interested in the communist part of it but in their attempt to recognize the rights of the million Protestants in Northern Ireland to their British identity. There was a letter outlining these arguments sent to a national newspaper, signed by a number of people, which was quite a provocation. My signature was among them, not that anyone would have noticed except at home, where they were pretty surprised.

INTERVIEWER

What did you do after you graduated?

TÓIBÍN

I went to Barcelona the day after my exams. I didn’t even wait to graduate. I found work quickly, at the Dublin School of English. Gerard was around for a while, too, but then he went back to Ireland and I was alone in the city. The heat that September was astonishing. I’d never encountered anything like it. I arrived two months before Franco died. I watched a society transforming itself. I was at all the marches after his death. And the city was so beautiful. The alcohol was so cheap—brandy, Cointreau, wine, beer. On the weekends, I would go to classical concerts. I saw The Valkyrie for the first time in Barcelona. The American institute and the British institute had really good libraries, so I was reading everything I could find. I remember being systematic—you know, Forster from beginning to end. Middlemarch and then the rest of George Eliot.

And there was the small question, which came up very quickly—I’ve written about this in a story called “Barcelona, 1975”—of cruising. The men I met were incredibly good-looking, and really funny and likable. Everyone was twenty in their world, and I was twenty. There were no gay bars and no rules—it wasn’t a culture. Nobody knew to connect cruising to anything—to music, to disco, to gay rights. It had no roots anywhere. It was a lot of fun at the time. It was a lot of fun even when you thought about it later, actually.

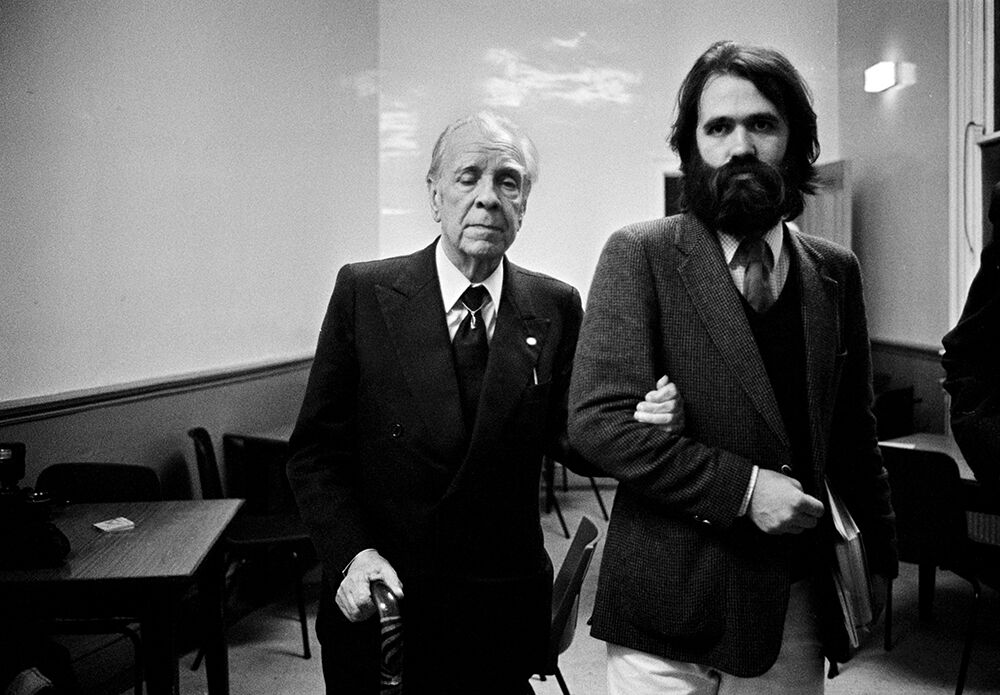

With Jorge Luis Borges at the Mansion House in Dublin, June 1982. Courtesy of Colm Tóibín.

INTERVIEWER

Were you writing in Spain?

TÓIBÍN

Absolutely nothing. I mean, not a word. Not one poem, and I found the very idea of fiction absurd. Someone I knew was writing a novel, and I laughed because I thought the mechanics of a novel were just so ridiculous. I kept mocking him, saying, “Oh, and the spring came, and then they went …”

INTERVIEWER

How did you start writing fiction?

TÓIBÍN

Well, when I returned to Dublin, that first winter was very hard. All my friends had gone somewhere else or had settled down. I thought of going into the civil service or going into foreign affairs as a diplomat. I even did the exams for the civil service, and got called for an interview, but I didn’t show up—I stayed in bed that morning. It was around that time that I wrote some short stories that were no good. I sent them out and no one wanted to publish them, so that didn’t add in any way to the general happiness.

INTERVIEWER

I can’t imagine the stories were that terrible.

TÓIBÍN

No, really, they were no good. I found writing stories very difficult because I was trying to put so much information into the first page so that you knew who everyone was, and was always using the pluperfect. I couldn’t relax into it by working with an image. I didn’t end up writing short stories again until, I think, 2006.

INTERVIEWER

How do you feel about the pluperfect these days?

TÓIBÍN

You know, in the workshops I used to teach, there was always someone saying, “I’d like to know more about how they met.” I used to respond with the example of the first chapter of Pride and Prejudice—there is nothing about how Mr. and Mrs. Bennet happened to meet and happened to marry. At a certain point I put a ban on flashbacks. Please don’t do a two-line gap and give me, “Eight years before when they had first met, they had been … And they had had had …” Oh no, oh no.

INTERVIEWER

So how did you start really writing, then?

TÓIBÍN

Well, a friend from UCD, John S. Doyle, started a magazine called In Dublin. I began to go into the magazine’s office every day—which a lot of other people did who similarly had no reason to be there and who were just impeding progress, sitting around. It was very much like the national library sequence in Ulysses. The world of In Dublin was small—it was a clique, all of us trying to write really well for one another, and this meant the standards were very high. David McKenna, the features editor, would say, “Rewrite your opening,” “Rewrite your ending,” “Go home and do one more.” It was an intense period of drinking with people you were working with—if there was any book launch or reception where there were free drinks of any sort, the entire staff of In Dublin would descend. Obviously, the magazine didn’t pay much, but then I started to write for Hibernia and then for the political magazine Magill, which I eventually edited.

INTERVIEWER

What were you drawn to as a journalist?

TÓIBÍN

I was drawn to being in print. David McKenna thought that the stuff I was writing was too bookish, so he started sending me out on missions, like to cover discos—I’d never been to a disco. I remember the first sentence of that piece still.

INTERVIEWER

What was it?

TÓIBÍN

“All over the city people are full of desire.”

INTERVIEWER

Jesus.

TÓIBÍN

I remember watching David read that piece in his office. I was standing outside, and he started to jump up and down with laughter because I’d tried to rescue the article from that awful beginning by describing a girl vomiting in the street. It’s two in the morning somewhere off O’Connell Street, and the girl is just vomiting and vomiting. Her boyfriend—a gormless-looking fellow—is watching her, and eventually she turns, the vomit coming down her chin, and says, “Fuck you.” And I was there taking notes. I didn’t make any thing up.

And so it went on. I remember when the government introduced crazy laws about condoms. To get them, you had to go to a doctor, get a prescription, and go to a chemist. I came up with the bright idea of going to six doctors and asking for a prescription—the first and last ones I was to tell I was in a stable relationship, and the others I had to tell I just wanted to get my rocks off on the weekend—you know, I just wanted condoms in my pocket for when I was going out. One old-lady doctor went ballistic. Of course, then it became, Colm’s the condom guy.

INTERVIEWER

Would you say that, by then, you had found your style?

TÓIBÍN

It’s that deadpan thing where you’re never sure where the laughter is going to come from or where the sadness is. Yes, there was absolutely a style from the very beginning, and people used to tease me for it, saying, Could you write a longer sentence? But there’s nothing I can do about it. I’ve made every effort.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a sense of the origins of that style?

TÓIBÍN

I think some of it is fear—a fear of tone, that it’s got to be held in, that anything more would involve some sort of release. There’s an element of feeling that if I try to write a longer sentence, I will actually lose control.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever lost control of a novel or a character?

TÓIBÍN

No. I exercise a huge amount of it. There were moments, though, writing my first book, The South, when I felt I was simply waiting for something I hadn’t explored yet. One was the moment when Katherine is in Barcelona and it becomes clear that the guy she’s been with up to now in the novel is actually dead. I was in Portugal in a hotel room—and I had been there for some time and I was waiting for something to occur to me when I suddenly wrote, “Miguel, five years dead, I am in Barcelona now.”

I’d thought that there would be the funeral to describe and the rest of it, so couldn’t believe I was writing that without any lead-in. My father’s name was Micheál. I was right back in some area of grief, speaking out of a lament poem like Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire. “Miguel, five years dead, I am in Barcelona now. I want you back, that is what I want, I want you back.”

INTERVIEWER

Where did the idea for The South come from?

TÓIBÍN

While I was working and drinking in Dublin with all these other people the same age who were all doing the same thing, I’d sometimes go back to Enniscorthy on a Friday night. It came as an enormous relief being there until Sunday, seeing the older relatives, being part of that old world. There was something about the difference between the two places that struck me. I recall that I once saw a woman on the train going to Enniscorthy from Dublin who didn’t look like other people—she looked more like an artist. I wondered who she was, and I began to imagine her.

I think I was also drawing on the artist Camille Souter—if I knew she was in Dublin for an opening, I would go and sort of study her. Dublin was, in some ways, a very drab, conservative sort of place, except for the painters, who stood out in the way they dressed, the way they lived, the way they related to Europe. So I began The South with the image of somebody coming home after a long period of being away—somebody different, who was being met off the train—and then I circled over the whole world of Barcelona that I’d been a part of. My big breakthrough was when I decided to move the story back a generation so that rather than being a novel about me going to Spain in the seventies, it was about someone of my parents’ age going in the fifties. Once I did that, I was in a space where I was completely comfortable.

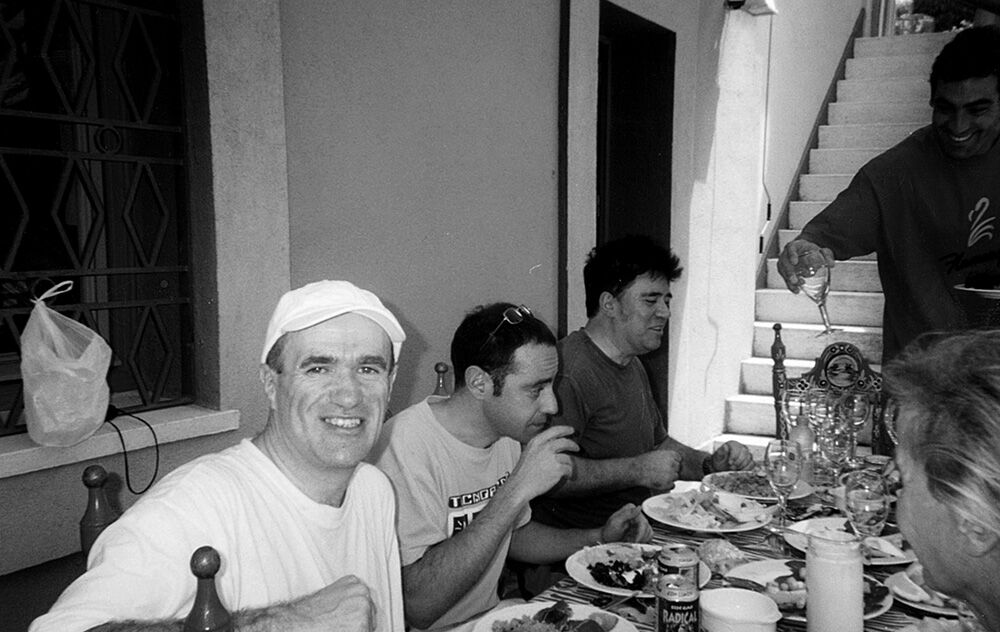

At left, Tóibín at lunch at Pedro Almodóvar’s house outside Madrid, 2000. Courtesy of Colm Tóibín.

INTERVIEWER

Why was it more comfortable to write about the past?

TÓIBÍN

I had been attempting to write stories about my generation, about the people I knew, on those streets in Dublin. But I couldn’t find a shape for that. I couldn’t find a tone for that. There was very little texture or density, for me, in the lives of the sort of people who were maybe working in the civil service in Ireland and reading Iris Murdoch novels and attempting to have dinner parties. John McGahern has written about this—how there’s a lack of an established set of manners among people born in the fifties in the Republic of Ireland. You couldn’t have a dinner party, because someone would get really drunk, the food would burn—it would be awful in some way—and trying to dramatize it would itself be futile.

But once I went back in time, I was at home. Another breakthrough happened with the chapter that came to be called “The Sea.” I began to write—“The sea. A grey shine on the sea”—and once again I thought, in surprise, Fuck. It brought me back to those small holdings along the coast in County Wexford. I realized that was something I could work with again.

INTERVIEWER

The title The Heather Blazing is very Wexford.

TÓIBÍN

I was brought up in a housing estate on the edge of Enniscorthy, and you could see Vinegar Hill directly from the house. The town was effectively the battlefield of the Rebellion of 1798 and the rebels’ last stand was on Vinegar Hill. People would sing that song written for the centenary, called “Boolavogue,” which became a rallying cry around Irish nationalism in the early twentieth century—“A rebel band set the heather blazing …”

INTERVIEWER

Were you working out ideas about nationalism in the novel?

TÓIBÍN

In a way, yes. When I was editor of Magill in the eighties, I was at one remove emotionally from current affairs. I felt I needed to always have my own project, a writing project, so, for about a year, I worked on a history of the Irish Supreme Court. Some of the senior judges were open to being interviewed off the record—Brian Walsh, Rory O’Hanlon, Niall McCarthy, all from the Fianna Fáil side. They were very conservative—let’s just take that as a given—but I found them to be very easy to talk to and very interesting and very polite. They reminded me of home, of my father’s family.

I was interested not only in what they were telling me about the law but in their manners. When I discovered that they would go home in the evening and spend a few hours alone writing a judgment and rewriting it—and that they based their judgments on previous judgments, which they would have to consult—this seemed to me very close to the business of writing fiction.

I remember telling the journalist Mary Holland, whom I was close to at that time, about my idea for The Heather Blazing as early as 1983 or 1984. Writing the novel was a funny process of grafting together bits from my childhood—the names of real shop owners, a Christmas dinner from memory, visits to my aunt—and from my father’s life. I was writing about a very dark time in the eighties. The abortion referendum, the arguments about divorce and church-state relations—those were burning questions that the judge’s children in the novel care about.

Eamon, the protagonist, is one of the first Fianna Fáil judges—he’s an architect of the attempt to separate the politics of the Republic of Ireland from the Troubles in the North. He’s immensely conservative, but he’s not monstrous, not a hypocrite. It’s not like he’s having an affair in the middle of a divorce referendum. I was determined that Eamon wasn’t going to be one of those fathers in Irish fiction and drama who shout and drink.

I share a background with Eamon—his father was part of the War of Independence, like my father and his other brother, who, if a house was to be burned, was sent to Dublin by the local insurgents to seek permission from the IRA leadership. My uncle would spend most of the day in a library in Dublin and then slip away, moving invisibly, to seek out the leaders, and then make his way home. I was interested in the slyness, the stealthiness of that. Eamon himself, in the quiet republic that his father and uncle fought for, is a very quiet fellow himself, and he wants a very quiet life, and he gets one. But it’s not enough.

INTERVIEWER

Your first two books wrestle with a certain trope—Katherine abandons her child, Eamon’s mother dies when he’s a baby. What do you make of that?

TÓIBÍN

I suppose those months of being left with my aunt, all those years before, got into the very marrow of the narratives. I was simply incapable of writing a book that didn’t deal with this abandonment—with being alone with no mother in the house. On some level I must have been conscious of that, but I was busy with the stories—perhaps if I’d thought about it I would have stopped myself from writing them. The speed with which I wrote The Heather Blazing means that it’s probably the most direct telling of the grief and numbness that poisoned not only that year but the years that came after, and left me feeling helpless.

I was behaving, for all intents and purposes, like a very competent person—I was writing my books, I was meeting my deadlines, I was paying my mortgage—but it was always there. In The Blackwater Lightship, it wasn’t even a shadow or an undertow. It was actually the entire backstory of that book, which was modeled on the story of Orestes, Electra, and Clytemnestra, but was also personal.

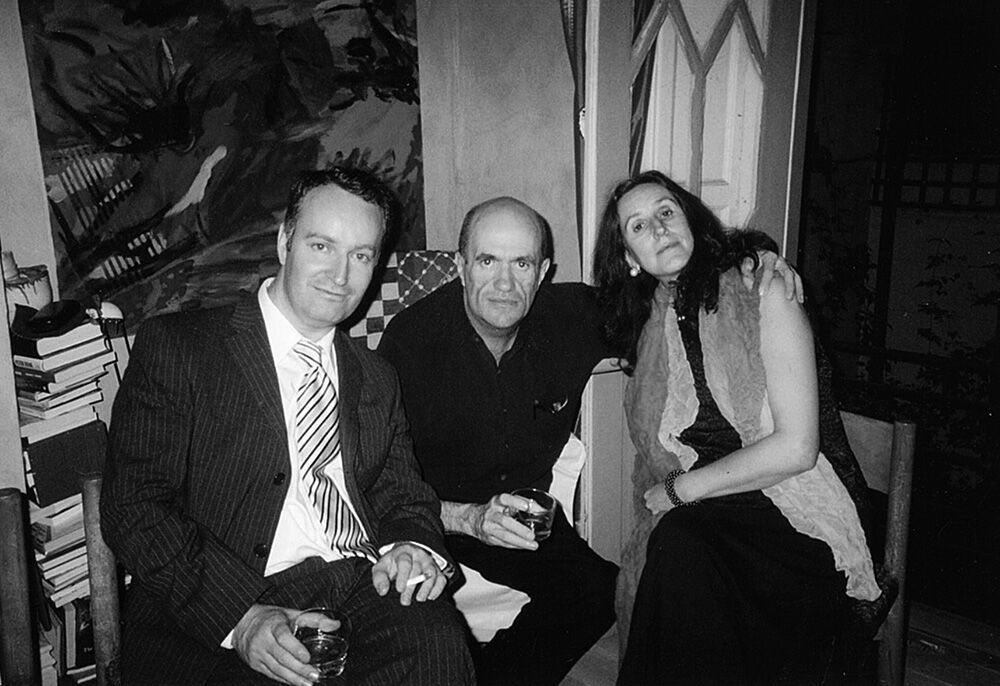

Tóibín, at center, at home with Andrew O’Hagan and Catriona Crowe, Dublin, 2001. Courtesy of Colm Tóibín.

INTERVIEWER

Do you believe writing can be therapeutic?

TÓIBÍN

It’s not far from therapy, in that you are called upon to identify a drama, a source of pain, and create a metaphor for it. You’re dealing with a set of unreconciled experiences—no matter what you do in a novel there’s a secret DNA of whatever it is that you’ve suffered. You can recognize these experiences, and you can exploit them, very coldly, but it’s not as though you reconcile them by writing about them.

I think if you’re not working, as a novelist, from some level of subconscious pain, then a thinness will get into your book, and you won’t know why. Somehow, with these great unresolved personal matters, what you’re doing is dramatizing them, often without knowing exactly what the terms, the parameters are for doing so. It doesn’t help you. Then again, I’m not sure therapy does either.

INTERVIEWER

Not all readers would notice the mythological skeleton of The Blackwater Lightship you mentioned. Are we meant to?

TÓIBÍN

I’d been thinking for ages as to how you would make a contemporary version of that story—the sister, the brother, the mother, the dead father, and the grandmother as a chorus. I was drawn to Orestes, the man who’s been away, who plays a terrible joke on his sister. I had just edited The Penguin Book of Irish Fiction and noticed how hard it was to find a scene of domestic harmony. You have to go back to The Vicar of Wakefield before you find a happy family, but that book is set in England and that happiness is unraveled. You go from the John McGahern novels to Mary Lavin’s widow stories to John Banville to Patrick McCabe and there is no stable domestic world. I was wondering whether it would be possible to create a happy marriage in an Irish novel, with a very orderly and very easy home life. Those kitchen scenes with Helen and her husband in The Blackwater Lightship are almost deliberately created to break that mold of domestic strife. That novel really is so domestic—the making of tea, the setting of the rosary, the ritualizing of each day. It needed some grandeur attached to it or it would have become a kind of soap opera with six people over seven days. The mythological premise helped steel my nerve at times when the emotions seemed high and my tendency was to bring it down a notch—steel my nerve not to bring it down a notch, especially in Helen’s anger toward her mother.

INTERVIEWER

Is the presence of AIDS, in that novel, a part of that mythological framework?

TÓIBÍN

AIDS doesn’t stand for anything in the novel. It’s not a metaphor. I was concerned that writing about it could appear exploitative, or that it could seem like a tragedy that was bound to happen. It was important that the virus come as a great shock to the characters, because it was one for us—for gay people in Ireland. Because the country is so small, there were young men from rural Ireland who were disappearing from the gay scene in Dublin. People would just say, “He went home.” Ah, shit. You realized what it meant—that a guy who had been at every disco, who had been all around the place, was sick and had gone back to his family.

INTERVIEWER

Both The Story of the Night and The Blackwater Lightship have several scenes of pure happiness—I think The Story of the Night has ten. That’s a lot for an Irish novel.

TÓIBÍN

A gay novel and an Irish one have a problem in common. When E. M. Forster was writing Maurice, he talked about how a gay love story would have to end in mutual suicide to be accepted. And, I suppose, the Irish novel would need to end when someone burns the house down.

It was very important to me that at the beginning of The Story of the Night we take in Richard’s life, his coming out, his family, his work, in a sort of picaresque way. This is not the story of a gay man with AIDS. It’s the story of a gay man who later on, to his own deep surprise, finds himself infected with HIV. The party in The Blackwater Lightship serves a similar function. I remember seeing that film The Deer Hunter—I disliked it intensely, but the opening half hour, which takes place before Vietnam, when they’re all having a wonderful time, stayed in my mind. I wanted to create the impression that the novel was going in another way. Because we start with this happy family, you think this is going to be the story of the death of a child, the breakup of a marriage, something like that.

INTERVIEWER

The reader and the protagonist are in it together.

TÓIBÍN

That’s right. I remember the first time I read The Portrait of a Lady, I thought that it was a book about national forms of style. There was so much about stylishness, and indeed the stylishness of the book was something I really noticed. Then I realized that it was about something else. I was reading a pure novel of morality and treachery—almost evil. I was astonished by the plot and by the idea that I could not read these people and neither can Isabel.

INTERVIEWER

Why do you think you were so drawn to James as a subject?

TÓIBÍN

It wasn’t like I could have picked any writer. I couldn’t have written about George Eliot, for example, because her politics and her role in English society and her sexuality seemed very clear to me. No mystery to explore. The same would have been true of Joyce, or of Wilde.

Part of my interest in James was not only that he was secretly gay but that he was a mass of ambiguities. As I began to imagine the novel, there were a number of biographers, particularly Fred Kaplan, who were revisiting James with an emphasis on his sexuality. And there were critics who wanted to stop the misreading of him as this elderly bachelor who knew nothing about life. The campaign, I suppose, was to move him back to the center, and the only way to do that was—crudely put—to queer him. I was very uneasy about this effort. I had my own reasons. I felt that if you’re gay, that would not explain everything about you as a writer.

Once I had James in mind, the decision to write about those five years in his life, 1895 to 1900, was easy. In that period, James wrote only one great work of fiction, The Turn of the Screw, and did that in the strange time between signing a twenty-year lease on Lamb House and moving into it. Once I realized that a piece of fiction like that had come out of a sort of rawness, a moment of emotional turmoil for James, then I could work.

INTERVIEWER

What effect did the success of The Master have on you?

TÓIBÍN

It opened up a lot of space for me, especially in America. The novel was reviewed in The New Yorker by John Updike, with a photograph by Richard Avedon. I liked Avedon. He’d already taken my photo once, on a day in 1994 when he’d photographed four other people before me and I was to be the last, but the others had bored him and he started packing up. I decided that this was too great an opportunity to lose, so I tried putting my hand into my mouth— I thought that maybe this might interest him. I tried not to vomit, but just to keep going with my hand in my mouth. He said to me, “Is your work very dark?” I said, “Oh yeah.”

INTERVIEWER

You entered a phase of intense productivity after The Master. Did it feel like a golden period?

TÓIBÍN

It was a noisy time. I did a lot of readings and talks. I began to teach. But it was also a time when my mother and my younger brother died. Nothing felt golden.

I had been working hard on the manuscript of The Master, and there was a huge amount of rewriting. I found that when it was over I still had that energy without having a reason to work. One of the results was that I began to write short stories again. I was in a hotel in Bucharest when I wrote the first sentence of a story called “A Priest in the Family” on a little notepad beside my bed. I began to write poems again, too.

INTERVIEWER

You also wrote a play, The Testament of Mary (2012), and got a Tony nomination for it, but it was a flop on Broadway.

TÓIBÍN

It was a challenging show. If you’re coming in from Kentucky on your holidays, you’re going to take in only one Broadway show, and Bette Midler had just opened around the corner. The image on the poster was unfortunate—Fiona Shaw with barbed wire around her mouth. Oh my God—that barbed wire! I remember when it closed, Deborah Warner, the director, convinced them not to destroy the set. She persuaded the Barbican to take the play and it actually had a successful run in London.

INTERVIEWER

The novel you wrote from the material of the play has a very particular tone—there’s an ancient timbre to it. How did you create the voice of Mary?

TÓIBÍN

It came from the idea of a woman surviving loss, one who has been silent and now begins to speak. I would call that voice first-person staccato—a particularly high-toned, strung-out, take-no-prisoners sound. There’s no stopping for rest, no sense of relief. There’s not even much iambic sound in the prose. It’s much more spondaic, trochaic. It was there in The South as well—Katherine is strung out with either sleeplessness or with too much coffee—and it’s there in a few of the short stories in The Empty Family (2010). The problem with the first-person staccato is that the possibilities of devolving into a kind of self-parody are enormous, so it has to come from something deeply felt, emotionally pressing. The idea was that Mary was acting out her own story, putting shape to it—that this would be the only time she would.

In the autumn of 2000, I taught a course at the New School called Relentlessness, and I chose to teach translations of some ancient Greek texts, and Joan Didion, James Baldwin, Ingmar Bergman, Sylvia Plath. The class was very useful because it gave me a bedrock of theory about what this sort of work was doing. I think it has the power that comes from powerlessness, a tone or richness that comes from not being able to own anything else. Once you have that certain authority, you can actually write a plainer prose.

INTERVIEWER

Has teaching been important to your writing?

TÓIBÍN

I have to say I’ve gotten nothing but pleasure from the classroom experience. I enjoy trying to work out what is truly going on in a story or a novel, or ways it could be improved. For many years, I’d spend a semester a year teaching in some new place. That was always a serious uprooting—you’re usually in a sublet in unfamiliar surroundings, under certain pressures to deliver, out of your comfort zone in every way. Your bed is not your own bed, and you’re still on, you know, Ireland time. I think in every one of those semesters some piece of fiction, quite dark, quite unexpected, would emerge. It was an annual descent into some very frightened place—if I started teaching in January, by April I would have begun a story whose tone was especially forlorn. That opening sequence of House of Names (2017) is from one of those episodes. I got stories like “One Minus One,” “The Color of Shadows,” and “Sleep” in that way.

Brooklyn, too, came indirectly from one of those times. I’d written the first chapters of The Master and of Nora Webster in the same season, the spring of 2000, when I was staying with Beatrice outside Florence. It was pretty clear to me that at some point I was going to come back to Nora Webster, but I kept postponing it, in part because there was a worry that I didn’t have any obvious drama for the novel, that it would be a slow book. Then, in 2006, I went to Austin, Texas, to teach at the university. Everything was ideal—it was a very low workload and it was a very nice place to live and all of that. But I grew uneasy, really as soon as I arrived, especially in the mornings, about being away. I had the date I was leaving in my head all the time. In a way it was very low-key homesickness, which I hadn’t had before.

When I came back to Wexford, I decided to reread the first chapter of Nora Webster with a view to going on with the book. It was one of those January nights. I was on my own in the house. On about page three there was a tiny story, something I had written based on an event that really happened in Enniscorthy—a woman had come to my family house, wearing all these scarves and a hat and coat, to visit my mother, who was recently widowed. I sat there and listened, which I would often do. When the woman left, someone said, “You know that woman’s daughter? She came home from America and she didn’t tell anyone that she was married”—because she felt that it would break their hearts when they realized she had to go back to America. This business of leaving, coming home, leaving—what I’d been doing for a long time—had made me think of home as a mirage. That’s what I was working with in Brooklyn.

INTERVIEWER

Eilis, in Brooklyn, has a flintiness to her. Did you know who she was when you started out?

TÓIBÍN

I didn’t begin with a specific sense of her—it was merely that she is the sister of someone more powerful, that she doesn’t have a job and therefore she’s very vulnerable, and then that she has to make her own way. I was taken with James’s Washington Square—which is a novel he himself didn’t really rate, although the character of Catherine Sloper is a remarkable creation—and, going back further, with Fanny Price in Mansfield Park. I was thinking about the idea of a submerged figure, someone who doesn’t radiate light but rather lives in the shadows, and whose time in the shadows can make depths of feeling really matter to the reader—stubbornness, love, feeling left out, wanting to be included. Eilis has to be very careful all the time, so she quickly works out a way, almost silently, of having people look after her. It’s a form of self-assertion, but a very reduced form, and it’s so interiorized that it’s not plain even to her what she’s doing. Hers is an immigrant’s struggle to make sure that everything she does helps her fit in or learn how to function. And obviously, this all can be broken down very easily—by a letter from home, say.

The question that interests me is to what extent the personality under these pressures is—and I hesitate to use this word—authentic. To what extent is a feeling real if it’s experienced in an effort to keep things from falling apart? That romance with Tony, for instance, has all the elements of a real romance, except it isn’t one. The novel is an anti-romance, about someone who has been so churned that their feelings can’t be trusted.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a difference between writing about fictional and real people? Did you feel, with The Master and The Magician, that you had found the real James, the real Mann?

TÓIBÍN

Not for a moment. My idea would be, I suppose, that there’s no such thing as the real anyone. When James was in society, he tended to be guileless and very funny. In private he wasn’t. That’s what I’m like, too, at least on some days, and I could play with that. With Mann, I saw a story that would require a textured, controlled study of something that could not easily be defined. The most important thing was that the man himself be missing from his own life, be—it’s almost too cliché to say—a man without qualities, a man whom you would have to make present by implication as much as by dramatizing anything he was doing or saying. Mann is a ghost in the novel—he’s barely there. He doesn’t speak much, he just notices and responds. Also, he always has quite a lot of money.

INTERVIEWER

Why is that important?

TÓIBÍN

Mann is so self-concerned and comfortable that global events don’t especially occupy him. It’s essential that he doesn’t see and that the reader doesn’t think about the fact that the First World War is coming or the Munich revolution is coming, or the rise of Hitler, the inflation, et cetera. Most people don’t know what’s coming, but Mann seems particularly not to know. That’s why the only structure that would work for The Magician was a biographical one that moved chronologically through his life—it had to occur in real time.

That distance was important to me, the fact that most of the action happens outside of Germany. I don’t have many ethical problems as a novelist—I don’t do ethical problems. But when I covered the trials of the generals in Buenos Aires in 1985, for example, I realized that The Story of the Night had, emphatically, to be set in the aftermath, in the strange time after. I was not going to fictionalize the detention centers, the tortures, the disappearances. To enter into these moments with the methods I use would be to desecrate the thing and to miss the point. It would be to constantly feel that I was not up to it and that a historian was needed, badly. I was not going to do it, because the way I work is minimalist, ironic, whispering, sort of uncertain.

INTERVIEWER

Nora Webster is perhaps your quietest novel—Nora is almost entirely in the shadows.

TÓIBÍN

I tried to trust what I was doing. If I was going to write a book that was to be immensely quiet, then everyone would just have to put up with that. It would have been very difficult to do if it were my first novel, but the success of The Master and Brooklyn meant that I was in a position where I could. More than that, I was concerned that if I tried to write plot-led novels that were made to be turned into movies, I would lose something essential. Just going back to a much more reduced set of colors satisfied something in me.

In 2005, I wrote a long short story, “A Long Winter,” which I probably should have published on its own as a book. It was about a death in a storm, and it had elements of a folktale, or a Schubert song—a young man goes out into a snowy landscape every day to find his mother’s body.

I had bought a plot of land in the high Pyrenees, and the day I bought it someone pointed out that there was, on the land, a little ruin of the house where the previous owner’s mother had been born, and that she had died in a storm one day walking back to the village. That can happen in the high Pyrenees—a beautiful winter day will become treacherous, and when the snow comes it will all come in half an hour. I didn’t begin the story thinking, This is a metaphor—this is a way I will be able to approach the material of Nora Webster.“A Long Winter” came of its own accord. But I was surprised when it was finished at how close it was to what was happening emotionally in the novel I was trying to write. The configuration was the same.

In the Atacama Desert in Chile, 2021. Courtesy of Colm Tóibín.

INTERVIEWER

If that is the case, who is it that’s buried under the snow in Nora Webster?

TÓIBÍN

Nora Webster. It is as though in becoming a widow she has moved away from her children, which creates in her elder son, Donal, a need to watch her as though she, too, might disappear. Every little scene in the book is in a sense a quest to find her. I wrote most of it after my mother’s death and after my younger brother’s death. There was a sense, in attempting to get it down, that I was bringing back their ghosts.

INTERVIEWER

I was struck by the scene in which Nora questions her aunt Josie about what has happened to the boys while she was away. She sees that they’ve been traumatized. That moment felt to me like an elegy for an Ireland that might have been, had parents and figures in authority been able to protect their children better.

TÓIBÍN

I have to say that as I was writing the book I had no concept of that, no sense of it and no interest in it. Of course, Nora is not a typical Irish widow. She does have some features or some characteristics that are quite extraordinary and that she doesn’t really know what to do with. There’s a rage in her, and sometimes that makes her behave unfairly. I was thinking only about her character. If you place an intelligent and complex woman in a provincial place and put her through this experience, what will she do? I think that’s how novels become national novels—by accident.

INTERVIEWER

The ending, more than that of any other of your novels, took me by surprise. Nora tells her younger son, Conor, that she’ll be singing Brahms’s German Requiem in the choir. He nods and goes to his room, and then we have her alone—“the silence broken only by the faint noises from Conor upstairs and the crackling of wood burning slowly in the fire.” No rhetorical flourish.

TÓIBÍN

No sleep, either. I wanted a conclusion that would lift her out into the future. I had thought that the book would end with the performance of the Brahms—I even attended a community rehearsal in London where we rehearsed all day and then performed the German Requiem with sheet music. I was less than useless, but that was not the point. I’d been preoccupied by the figure of Lorraine Hunt, who had been a soprano but all of a sudden had emerged as this extraordinary mezzo, which can happen with age. I was interested in the fact that, around the same time as she was transforming herself from soprano to mezzo, which is a big move, her sister had died. I didn’t end up dramatizing the Brahms concert directly, but I wanted to show that Nora was doing something for herself. Of course, there’s also the sense that Conor isn’t that interested.

INTERVIEWER

And where’s Donal at the end of the book?

TÓIBÍN

Is he not in the room, watching?

INTERVIEWER

No.

TÓIBÍN

Ha! I think he’s at school.

INTERVIEWER

I suppose I’m asking because—you are Donal, aren’t you?

TÓIBÍN

Yes.

INTERVIEWER

Do you also inhabit the character of Conor, the younger brother?

TÓIBÍN

No. The only way I could work was if I was faithful emotionally to what I experienced in those years. Conor is a more unformed figure in the book, more even-tempered. He is like my brother Niall was then. Donal is the one—because he’s older—who has a more complex response all the time. He’s having trouble at school, having trouble with his speech.

INTERVIEWER

When did your stutter disappear?

TÓIBÍN

It hasn’t. If I’m not sleeping enough, it will come back. There was a time not long ago, when I wasn’t sleeping properly, that my students must have noticed that I was sometimes simply not able to say a word. But it doesn’t happen much. I have worked out ways of dealing with it. It’s masked, it’s disguised, but it’s not gone.