Issue 237, Summer 2021

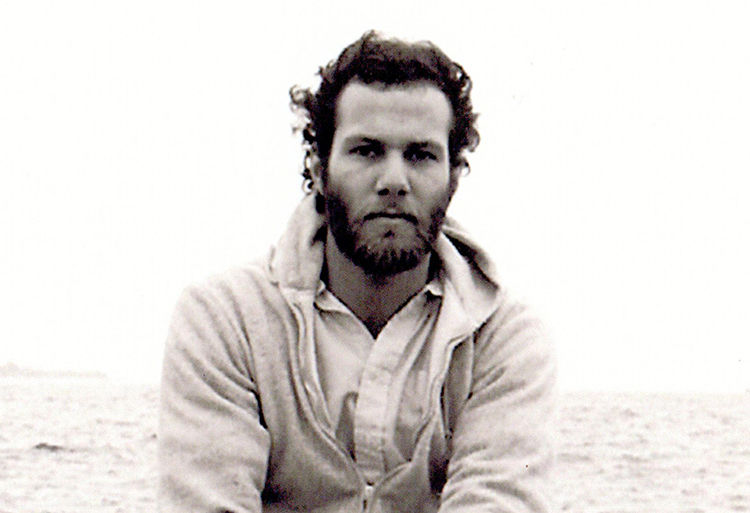

Chast in Washington Square Park, New York City, 1966. Photo courtesy of Roz Chast, with thanks to Blow Up Lab in San Francisco.

There’s a certain type of comedy in which the comedian will examine and even dismantle a joke in service of the truth. I don’t think it has once occurred to Roz Chast that truth can possibly exist outside of funniness. To her, the truth, even in its barbarism, is screamingly funny. And, of course, if something isn’t funny, it isn’t true.

One can divide comics artists into two categories: storytellers, who use drawings in service of their narratives, and illustrators, who take care with things like intricate, full-color cityscapes, and whose work is read with the part of the brain used for looking at paintings. Chast lands in the storyteller camp, because the story is what she cares about most. But she is a nonlinear and deeply visual thinker, equally likely to deploy line and color as a string of words to tell her stories. Her pictures are not illustrations of the things she’s saying but story itself. Chast’s cartoons—populated by disgruntled men; horrible storefronts; dumb, square-toothed horses; gourmandizing pigeons; bottom-of-the-barrel bourgeoisie in optimistic little hats—are, at their heart, about deeper things: loneliness, family, the impossibility of maintaining order, and the batshit, bonkers ridiculousness of life.

Chast once described William Steig as “not a minimalist”—an artist for whom every sofa, wall, and shirt was a blank canvas on which to explore pattern and color. Chast, who draws with Rapidograph pens and then adds watercolor, is the same way—she is a details person, as delighted by the gratuitous joke in the title of a book in the background of a cartoon as by the slam-dunk punch line in the caption.

Chast was born in 1954 in Flatbush, Brooklyn. An only child, she grew up with her mother—an intensely decisive assistant principal—and her father—a sweetly anxious French and Spanish teacher who couldn’t screw in a light bulb. She went away to college at sixteen, first to Kirkland College in upstate New York, and then to the Rhode Island School of Design, where she studied painting and was benignly ignored by her peers and professors. She came to Manhattan after college with a portfolio full of cartoons and no backup plan. I imagine her wading through a sea of older Jewish men, the career gag cartoonists, many of whom had cut their teeth writing for Charles Addams and now traveled the weekly cartoon circuit—The New Yorker, Playboy, there were others. I doubt these men knew what to make of young Roz and her drawings. Most cartoonists have specific-looking characters. Chast’s are defined, if anything, by their amorphousness. They are blob-faced, with bad posture and changeable features. Awkward, out of place, in the way. There is a 1997 video clip of a crowd of these men milling about, with a small, fearful shape making its way behind them, toward the exit. That was Chast, who has been faithful to The New Yorker ever since she sold her first cartoon there.

After her parents died, Chast published a graphic novel, Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant? (2014), about the awful experience of caring for them in their decline and about who they were, as parents and as people. Created in a startlingly intuitive mixture of handwritten blocks of text, comics, and cartoons, it catapulted Chast to a new level of acclaim, reaching the top of the New York Times best seller list and winning a National Book Critics Circle Award. It has been followed by three other graphic novels—Going into Town (2017), a loving and funny book about what to do in New York City, and two books cowritten with Chast’s old friend and collaborator, the humor writer Patricia Marx.

I met Chast for this interview uptown, at her studio apartment, which she started renting when she won a Heinz Award and uses to escape Connecticut. Chast has the watchful air of someone who grew up surrounded by elderly New York Jews: like Max in Where the Wild Things Are. Manhattan is still her refuge. Her apartment is small and nicely spare, and contains some beautiful outsider art (why is it even called that?) involving birds, and a pair of slippers, like the room in Goodnight Moon. The first time we spoke, Chast was in the middle of a tour to promote You Can Only Yell at Me for One Thing at a Time (2020), a book of accurate marriage vignettes she’d written with Marx. The tour doubled as a musical junket for their extremely serious ukulele band, Ukular Meltdown. We had the first half of our conversation in person in the apartment, and the second half on the phone during the COVID-19 lockdown.

INTERVIEWER

What are some things that always make you laugh?

ROZ CHAST

Sometimes it’s dumb things, sometimes it’s a stupid, pratfall-type thing—like, some Buster Keaton comedy. Or sometimes it’ll be The Office, the original British series . . . Certain sitcoms, but not the scripted sort of laughs, the punch line thing—God, I hate that! I hate when I feel the construction of a joke. It makes me sad.

INTERVIEWER

Oh, interesting. Do you not like Seinfeld?

CHAST

Oh no, I like Seinfeld. It’s more like when you watch some sitcoms, and you can feel it—setup, setup, setup, punch line, setup, setup, setup, punch line. I cannot bear it. And I don’t know why, but things that are very, very earnest—immediately, I want to make jokes. I don’t know what it is.

INTERVIEWER

Do you want to make jokes because you’re angry and want to pinpoint the hypocrisy of it all, or because you’re genuinely amused by things like earnest people?

CHAST

I think there’s probably . . . deep down, there’s anger, but usually it’s because really earnest things make me laugh—and it’s like that song, “I am woman, hear me roar,” and I think [high-pitched], I am woman, hear me squeak. It’s very hard for me to be very serious. It makes me sort of embarrassed.

INTERVIEWER

Cartooning feels like the one of the least “hear me roar” of the arts. How, if at all, is being a cartoonist different for a woman than for a man?

CHAST

I had to make up my own way of making cartoons. I knew that I didn’t want to imitate male cartoonists—and they were almost all men at the time—whether they were traditional cartoonists or underground cartoonists. I don’t know whether this was because I am female, or whether that was just my personality. A friend of mine has a kid who is an artist. The mom is an artist, too. Sometimes my friend would try to show her kid a more efficient, better way of doing something, and her kid would say, No, I want to do it the child way. I completely identify with that.

INTERVIEWER

How does empathy enter into your art?

CHAST

Maybe empathy is a way of acknowledging that whatever feelings you have, other people are feeling those . . . they don’t necessarily feel the same way, at all, but they have feelings. And maybe, if you’re a person who wants to be as truthful as you can, empathy is also a way of trying to figure out how to say something difficult without making somebody feel awful.

Being funny can be complicated. I don’t want to accidentally make somebody feel bad. On purpose, I might want to make somebody feel bad. But I wouldn’t want to do it accidentally.

INTERVIEWER

When you make cartoons, do you feel like you’re channeling a persona? Like a comedian’s persona—it’s them, but kind of exaggerated?

CHAST

I don’t know if it’s exaggerated, but it’s a little bit of a pretending. But it’s not a different person.

INTERVIEWER

Where did that voice come from in you? Did it come naturally, or did it take work?

CHAST

I drew from the time I was a little kid, since before I could write. It’s always been a part of me. Putting together a cartoon always takes work, especially if it’s multipanel and there are different threads going on. But the part of me that suddenly finds the idea of omelet stations hilarious, I don’t know where that comes from.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think the relationship is between words and pictures?

CHAST

In my case, they are conjoined twins. They’re interconnected in a primary way. When I was at art school, and a painter, I missed the words, and when I write, I miss drawing.

I sometimes wonder—is it just that I’m so lazy that I haven’t become a better artist? You know, better at drawing cars, better at drawing this, at drawing that. But then I think about Sam Gross, who once told me that he had sold a cartoon about sheep, and so he looked up photos of sheep, but when he drew them from the photos to make them more realistic, they weren’t as funny. I don’t think a cartoon is just an illustration of a funny idea. The drawing style has to go along with the words, and be funny also. Like with George Booth’s drawings—they were really funny—his line is funny.

INTERVIEWER

I wonder whether what some people call “good art” is drawings of things as they are, rather than drawings of ideas. A realist painter will paint a person realistically. Whereas you draw the idea of a person. I’ve always felt way more connected to what you do than to what, say, Ingres does. Or a more florid cartoonist like Peter Arno, for that matter. I think your drawings are much more accurate, in the ways that matter in a cartoon. In other words, I think you are a very good artist. Is your refusal to follow “the rules” a form of honesty?

CHAST

I don’t know about “honesty.” I value ideas—which is a broad category, since it’s not just the joke, it’s the whole thing, the voice, the world it’s coming from, what the artist is drawing and why—more than craft-skill. Maybe that’s bad. I’ve seen lots of work that’s beautifully drawn but I’m so bored. It’s like someone has performed a difficult trick and now I’m supposed to applaud. Cirque du Soleil art. Wow, it must have taken years to learn how to twirl that hoop with your foot while you’re hanging upside down fifty feet in the air!

INTERVIEWER

Do you consider yourself part of a tradition of nonrealistic, feeling-driven artists? My—not very educated—mind jumps to Modernist painters like Matisse and Picasso, or the emotional, cartoon-like people in Chinese scrolls or on Greek vases. Then there are the messy indie cartoonists, Lynda Barry, R. Crumb, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Diane Noomin. What’s your lineage? Do you have one?

CHAST

I don’t know. I think I’m part of the messy lineage, though. Feel free to insert a smiley-face emoji, please.

INTERVIEWER

What tends to interest you most when you’re drawing a person? Or a thing?

CHAST

I love to draw interiors. I love detail. Pattern, little objects, a bowl of sucking candies on a table, the clutter of life . . . And I love to draw people, but they always look sort of schlubby. I don’t know why this is.

INTERVIEWER

Something I have noticed and love so much about your drawings is that your faces don’t necessarily have a shape, and your people don’t necessarily have a shape—they’re neither skinny nor fat. Those decisions leave room for expression.

CHAST

I’ve tried many times to draw glamorous-looking people, and it’s impossible. I have put fashion drawings on a light box and traced them, and the people still come out looking schlubby! This interests me.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever tried to follow “the rules”? In art school, did you try to be an artist?

CHAST

It was a very funny time in the art world . . . Minimalism, Conceptual art, Vito Acconci, Chris Burden, video art, this kind of serious stuff.

At RISD there was a group of boys that had started a cartoon magazine called Fred. I was the only girl drawing cartoons, as far as I knew, and I was so excited, and I submitted, and they rejected me. And then I cried—cried like a baby because it was so hurtful. I knew deep down that making cartoons was all I really could do. And I had tried to show a couple of teachers my work, to no avail . . . I wasn’t happy at RISD, but I’m glad I went, because I think it made me so angry—not just the Fred thing, but the whole experience of art school. By the time I got out . . . actually, by my senior year, I didn’t really care what any of them thought. I fulfilled my requirements to graduate, and I painted, but I didn’t care about my paintings. I was starting to draw cartoons, but after Fred I didn’t show them to anybody.

INTERVIEWER

How about the rules of cartooning? As a New Yorker cartoonist did you ever try to do a quick gag?

CHAST

I have, yeah. I sold one or two gag kind of cartoons. But there’s some very stubborn part of me that wants to do things my way. Maybe it has to do with having grown up where I never got my way, or because of being female, or whatever. I don’t take it for granted that I’m going to get my way, or that what I think is of any use to anybody, or of any interest. Just give me this tiny postage-stamp-size area. And I’ve been incredibly lucky that I have gotten—knock on a million pieces of wood—the opportunity to at least explore that, and to find out where it goes, and what am I interested in, and what is funny. To not have to conform to all the ways that people say, This is what’s important . . . And now you’d better . . . You need to do it this way.

INTERVIEWER

The risk there is that the rules change.

CHAST

Suddenly, the thing that you have learned to do perfectly—Conceptual art, Minimalist art, Josef Albers’s color theory—is out of fashion, and then you’re totally fucked, and you’ve forgotten what you wanted to do in the first place. The only thing I want is to figure it out my way, and to figure it out myself. Because it’s not like I’m a brain surgeon, where somebody’s going to die if I make a mistake. If something goes really wrong while I’m drawing, I’ll throw it away.

INTERVIEWER

Do you make multiple finished drafts and choose the best one, or do you throw things out midway when you realize they’re not working?

CHAST

Midway. Midway, or even a quarter or a tenth of the way. I think, No, no, no, this is wrong.

INTERVIEWER

Where do you feel it? This is very Alexander Technique, but where do you feel it in your body, when something’s not working?

CHAST

This is going to sound really corny, but in my heart, in the middle of my chest. I feel like leaving the desk and never ever coming back to it.

INTERVIEWER

You’d been out of college for two years when you first submitted cartoons to The New Yorker?

CHAST

Less time than that. I graduated in May ’77. I took around this illustration portfolio, and it was terrible—the experience and the portfolio itself. I got a few illustration jobs, but not a lot. I was drawing cartoons for myself and by myself, but didn’t think I could sell them. They didn’t look like underground cartoons and they didn’t look like traditional cartoons. I was just compelled to do them. The illustrations were awful: a pastiche of styles that were popular at the time. What I thought would sell, because I knew I had to make a living. At some point, I couldn’t bear doing the illustrations anymore and started taking the cartoons around. To my great surprise, editors were more interested in the cartoons. I started doing cartoons for the Village Voice, and for National Lampoon, and then in April ’78 I dropped my stuff off at The New Yorker, never thinking they were going to take anything, because that was not how I thought this was going to go. I thought, if I was extremely lucky, I would maybe get a regular space at the Voice. And then The New Yorker bought something from me, which floored me. And Lee Lorenz, who was the art editor—he did everything at that time, he did covers, he did spots, he did cartoons—told me to start coming back every week, and not just to drop off work, but to actually come in, in person, and that was very exciting.

INTERVIEWER

Did you keep submitting stuff at the Voice after that?

CHAST

I did. But then, at the end of that year, The New Yorker put me under contract. It was “first refusals,” so everything had to go through The New Yorker first.

INTERVIEWER

Did your work—and your life—change after you got the contract with The New Yorker?

CHAST

I didn’t consciously change my work, but I’m sure there’s an inevitability of influence. Especially back then, my stuff really stood out. Oh, you’re the person who does those drawings that don’t look like anyone else’s! I really hate/really like them! But my work didn’t change a ton. I have tried, my whole life, to stick to drawing what I think is funny or weird or interesting, or something that “reaches” me. There’s no other reason for me to do this. It’s certainly not the money or prestige. Haw haw.

INTERVIEWER

When you started at The New Yorker—and for a long time after—the cartoonists were predominantly male, and mostly older than you. What was it like being a young woman in that crowd, with a punky art school background?

CHAST

It was very strange. I felt a little like an alien, but I’ve always felt a little like an alien. I think there were many things that were weird about me for the old guys. Female, twenty-three years old, I did not draw like them and had no interest in drawing like them. I didn’t have a bone to pick with them or their work. In fact, I liked many of their cartoons and styles. I wanted to, needed to, do it my own way. Mostly, they ignored me. But eventually, some of the younger ones—Jack Ziegler, Mick Stevens, Bob Mankoff—befriended me. I thought of them as older brothers. They were all about ten years older than me, and also tall!

INTERVIEWER

Let’s talk about your relationship with Lee Lorenz. What was it like?

CHAST

He had basically pulled me out of the slush pile, and it was so unexpected and life changing. I felt incredible gratitude and awe. And I was intimidated by him. We would come in individually and meet with him, and the minute I said anything I would turn it over in my head and think, I’m such a fucking idiot—why did I say that? I’ll never sell another cartoon, and he’ll probably tell me to get out. He was all of, whatever, forty-five, and he seemed old, old, old. And I was so shocked that they wanted me to be part of the staff, of the staff such as it is at The New Yorker.

INTERVIEWER

Did you go to the famous cartoonist lunches?

CHAST

I did, and we had wonderful afternoons, after the art meetings. We would go to these weird divey sorts of places in the West Forties. Irish pubs. And there’d always be these red-faced businessman types at the bar having their midday shots or whatever.

INTERVIEWER

Who was there?

CHAST

It was the group that Lee brought in, pretty much. It was Bob Mankoff, who succeeded Lee as the cartoon editor. It was Jack Ziegler. Liza Donnelly. Sometimes Victoria Roberts. Michael Maslin very rarely came in. Mick Stevens. Michael Crawford.

I really liked all these people. I was never, ever part of a group growing up, either as a child or as a teenager. This was the closest I had ever come. And it wasn’t too intense or too close. We just wanted to spend time with each other after going through a week of working on batches in isolation, and then going through the awfulness of finding out whether you’d sold anything the previous week or not. And someone would say something that was so incredibly funny. Not “Ha ha, that was funny,” but where you cannot breathe. Jack Ziegler and I once had a laughing fit about the word bolus, which is a lump of chewed food. We laughed until tears. He drew me a cartoon about it, which I still have.

We would smoke. I would go through a pack of cigarettes. We would have drinks. We would hang out all afternoon. We would go to these places probably because we never knew if we would be four people, or six, or eight, or whatever. And it was Wednesday, so it was matinee day and the nicer places were full. The worst was probably a place called Kenny’s Steak Pub, on like Forty-Fifth and Ninth or something. It was really grim. Linoleum on the floor. And they had a radio station playing in the background. You could tell it was a radio station because in between the songs, there were ads. It was really bad.

INTERVIEWER

Where were the older guys? Did they get lunch separately? When I went to the cartoonist lunches, it was always Mort, Sid, Sam, sometimes George.

CHAST

There used to be the Tuesday group, which was the older guys, and the Wednesday group, which was us. The youngs.

INTERVIEWER

Did you grow up reading The New Yorker?

CHAST

Yeah.

INTERVIEWER

What was your favorite part to read or look at?

CHAST

Cartoons. The cover. Later, Shouts & Murmurs and Talk of the Town, before it became more about current events or celebrities or semi-celebrities. Before the pieces were signed. Sometimes they were completely off the wall, stories about a weird conversation a person had with someone who lived in their building. I loved those.

INTERVIEWER

Did you always want to be a New Yorker cartoonist?

CHAST

No, no. And it wasn’t that I didn’t want to be a New Yorker cartoonist, it was more that they liked this kind of cartoon, and they liked a cartoon with a gag line, and they liked cartoons that look a certain way, like Dana Fradon or Bob Weber.

INTERVIEWER

You mean a slick line and shading with ink wash—less of a focus on being funny, more on depicting a kind of imaginary everyday life of some middle-class, white, straight, non-Jewish American, like a John Cheever story.

CHAST

The work was more illustrationy, more like they knew how to draw cartoons. That’s why I felt I could not be a New Yorker cartoonist, because I didn’t know how to draw like that. So, when I submitted, I was not nervous, because I was sure they weren’t going to take anything. I did it thinking, Well, they use cartoons, and so, why not?

INTERVIEWER

You met your husband, Bill, at a cartoon meeting, right?

CHAST

He brought in this group of funny postcards. I remember there was one with a bunch of clowns water-skiing. They were, like, in a pyramid. [laughs] I don’t know! It was just an odd thing. And it was funny. And then we went out to see Eraserhead, a midnight show.

INTERVIEWER

What was it like having young kids and also being a cartoonist?

CHAST

It was hard. When they started school it became a little bit easier. But I did a lot of cartoons about being a mom, and about having kids. For me it was another source of material in a way. I don’t know if that sounds very cold—probably.

INTERVIEWER

Not to me. I’m thinking of having kids, but only for that reason.

CHAST

They are funny. Kids say the darnedest things. And babies have big round heads. They’re just like bowling balls, big old bowling-ball heads, and you have to support the head or it’ll, like, snap off, and you’ll be walking around saying, What happened to that baby’s head? I guess it fell off.

INTERVIEWER

Did you find humor in being a new parent? Or did you force yourself to find humor because the alternative was too dreary and grinding? Sorry, I’m projecting my own fears onto you.

CHAST

That could be said about everything for me. That if I didn’t draw cartoons, everything after getting out of bed would be too dreary and grinding. “What T-shirt shall I wear today? . . . I’m so glad we still have Muenster cheese in the house . . . And so to bed!” Aaaagghhh. Not that I draw cartoons every day, because, a, I am lazy and avoidant, and, b, in these COVID days, the day goes by very fast and sometimes it’s dinnertime and I realize I have done nothing but check my email. But in general, making cartoons is a way of avoiding feelings of pointlessness and despair and still not being too upbeat.

INTERVIEWER

In what particular ways is it hardest to balance life and work as a cartoonist with kids?

CHAST

The truth is, I’ve blanked out some of the earliest years with kids. Sometimes it felt like I was just putting one foot in front of the other. Get the kids through their week of school, get a group of cartoons—“the batch”—in.

INTERVIEWER

Did you draw with your kids?

CHAST

Yes. Not as much as I should have, probably. I had constant mother guilt. But yes. We always had plenty of art supplies around. If I wasn’t in the middle of a deadline panic, it was fun, because they come up with odd stuff. Sometimes I would interview them and ask them questions and write down the answers. “What do you think is inside the body?” “It’s like pipes.”

INTERVIEWER

You moved from the city to the suburbs when your kids were young. Did your cartoons change a lot with the move?

CHAST

I had different subject matter to write about. Learning how to drive, for one. I still draw about the strangeness of living outside of the city, even though I’ve been living in Connecticut for thirty years. Recently, I drew something about being in the backyard. Well, you’re in the yard—now what? I often feel that way.

INTERVIEWER

You can dig a hole.

CHAST

Yeah, I guess I could. I could dig a hole, or I could walk to the edge of the yard and then walk back. I mean, I don’t even know what to do back there.

INTERVIEWER

Forage.

CHAST

There are no berries in our yard.

INTERVIEWER

There are worms, I bet, if you dig.

CHAST

Yeah, I guess I could dig for worms.

INTERVIEWER

I’m making you sad. I can see that you’re becoming sad.

CHAST

I just don’t belong there. And it is sad, because I’ve lived in Connecticut three decades, and I still feel very out of place there. It’s not my habitat.

INTERVIEWER

Your habitat is New York?

CHAST

Yes, yes. E. B. White had so many great things to say about New York in his book Here Is New York. And he talks about—not the gift of aloneness, but he actually uses the word loneliness—the gift of loneliness. And being in New York . . . that brings me back to my childhood of being alone, and realizing that I am alone—but better. If I don’t feel at home on the Upper West Side, I will not be at home anywhere on earth.

INTERVIEWER

What do you like about New York, besides the loneliness?

CHAST

I like walking fast, and I like walking in the city. Probably, if there is actually such a thing as an endorphin, I feel endorphins from being in the city.

I like looking at people when I walk. I like going in and out of stores and looking at stuff. I like discovering things, and wondering about things. Like, on Columbus Avenue there’s this little shoe-repair store that’s this tiny little storefront that’s jammed between two big apartment houses, and I like the way it looks. It’s so interesting. You look down the street and you see two giant buildings. But between these two giant buildings is a six foot gap, and in that gap is this little one-story storefront and—

INTERVIEWER

Like a fairy tale.

CHAST

—it’s just so strange and so wonderful. And that’s why I like walking around in New York, because I see that, and then you can take the bus, or you can take the subway and have a weird conversation about Roman architecture or something with somebody. It’s really different from any other place I’ve been.

Like, once not long ago I was coming home on the subway, and I had this great conversation with this older guy, and we were talking about the subways when we were kids, and I thought, This is so funny, because I’ve felt this in the past few years—it happens rarely, maybe, almost never . . . camaraderie is too strong a word, but when I see older people on the subway, we’ll look at each other, and it’s something that transcends color, it transcends gender. It’s kind of like, Oh good, you’re all still here, too. Or maybe I’m making it all up, it’s all in my head.

INTERVIEWER

You wrote a book about New York—it’s sort of like a guidebook.

CHAST

I wanted to write a book about New York, but also I didn’t want anybody to think, This is going to be a definitive guidebook, where there’s going to be tons of information. I did not want to do that, because there are a lot of books like that out there already, and people who do it much better.

INTERVIEWER

When did you start to love Manhattan?

CHAST

I’ve loved Manhattan since I was a kid. Back then the idea of living somewhere not with my parents was too abstract, but as soon as I understood that at some point, I would live away from my parents, I knew that was where I wanted to live. Everything I liked was there, people on the street, museums, apartments, diners, stores, the park if you needed nature but didn’t want to deal with bears or hateful hiking trails where your alternatives are, a, walk on this trail or, b, get lost and die.

INTERVIEWER

How is city humor different from suburb humor?

CHAST

There is no suburb humor.

INTERVIEWER

Can I ask you about how you work? Where do you work? When do you work? How long does a cartoon take?

CHAST

I have a studio in my house in Connecticut. I find it hard to work in the city. I mean, I write stuff down, but I find it hard to sit and work. So when I come back to Connecticut, I will putter a lot. I putter, I procrastinate, I get my coffee and I go upstairs and take out my ideas, and I look at my ideas, and hopefully something gets me excited enough that I start sketching. But it’s not always clear. Sometimes you can sort of see it right away, and other times you have to do it like this, and then you try it like that, and then I try it with panels, and then I try it with a single panel, and then maybe the title needs to be changed, and there’s all these different iterations, and—I have to draw it several different ways to figure out the best way to express what I thought was funny.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have an idea and start drawing it immediately, or do you have an idea and think, I’m going to come up with six ideas before I start drawing?

CHAST

Monday is the day when I draw, so sometimes if I have an idea I’m very excited about, I’ll write it down, and then on Monday I’ll start with that one. Sometimes, if I’m excited about an idea, it’s almost, like, too excited. I have to calm down, because the drawing gets so fucked up . . . It’s ridiculous. But that’s better than not having an idea.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve told me that you keep ideas on scraps of paper in a box.

CHAST

Yeah. I have an idea box in my studio. It’s a shitty shoebox, and I think it says fedex slips on it. I mean, this will probably go in the idea box when I get home.

INTERVIEWER

You’re showing me a ukulele with legs and a face, and it’s very voluptuous, but not in the way one would expect.

CHAST

I’m not good at keeping a notebook. But I will keep the pieces of paper where I’ve had ideas and put them in the idea box.

INTERVIEWER

Do you clean out the idea box and take out bad ideas, or do you leave them all to stew?

CHAST

Periodically, the ones at the bottom I’ll toss, or I’ll look at them and say, No, no, no.

INTERVIEWER

Do you pencil before you ink?

CHAST

I do. But I pencil differently for roughs than I do for finishes. I’m still figuring everything out when I’m penciling a rough. There’s a ton of sketching and erasing and sketching and erasing. When I pencil a finish, most of that thinking has been done. I try to get everything where I want it to go before I do the inking. Also, for the rough, I might not put in every last detail . . . I’m thinking of the drawing in The New Yorker where the woman is sitting on the sofa in the hazmat suit, and there’s the TV in front of her, and there’s shelves and everything like that. I’ll rough in where the couch is, where she is, and then I’ll put the TV in approximately where it is so it doesn’t fall off the end of the page.

INTERVIEWER

How does color fit into your drawing?

CHAST

I love working with color. I like watercolors, I love watercolors, actually. I don’t really know how to use them. It’s that weird, stubborn part of me that doesn’t really want to learn technique.

INTERVIEWER

Watercolor feels completely out of control, and like some . . . kind of like jazz or fast dancing. Some people can harness the out-of-controlness, but I can’t. Do you feel that way?

CHAST

I have to really push myself to accept things. I’m doing the sky, and there’s this watercolory blob thing going on. I had to learn to not just accept that, but to love it. Because my instinct is much more about control, and about coloring in. And, in many ways, for me, coloring is coloring in—it’s like being a kid. I really use watercolors the same way a kid would use a crayon. With watercolor, you’re never going to be completely in control, but I like that. I enjoy doing the color digitally when I draw on my iPad, but sometimes it feels a little too predictable and slick. Also you can keep endlessly refining things and get too caught up in minutiae. “I need to spend the next three hours making this chair exactly the right shade of green.” No, you do not.

INTERVIEWER

How is working on a book different from working on cartoons?

CHAST

They’re similar to cartoons, but they’re also really different, because, cartoons, it’s like you get an idea, and then you draw up the idea, and then you’re done. And even doing a one- or two-page thing, I can sort of see the arc, and I can plot it out—I can hold it all in my head at one time. But with books, I don’t know where they’re going to go. They take a long time, and many, many wrong turns.

INTERVIEWER

When you’re working on a book, do you work in order?

CHAST

For me, it really is about having this idea of what I want to know. I have these ideas, but I don’t know how it’s going to all come together, and the only way to do that is to follow the thread, and sometimes the thread is going to go in one direction, and sometimes it’s going to go back and then it’s going to go forward again, and then sometimes it’s going to be in a terrible knot and I’ll want to run away from my desk, screaming—and I will. And then I come back, and I have to unpick the knot, and I’m still following the thread.

INTERVIEWER

Did you map out the book about your parents?

CHAST

No.

INTERVIEWER

It’s so tight. That was just life? That was a story that existed?

CHAST

I had an idea in my head of where it began. And where it ended. But then, when I was working on it, it changed. I mean, in my head, I felt like it began when my mother fell off the ladder. Which was my fault.

INTERVIEWER

No, it wasn’t.

CHAST

I know it wasn’t. And yet a part of me feels like it was. And I knew where it ended, which was my parents’ ashes in my closet. But it turned out, even when I was working on the book, that that was not the beginning of the story. And then the ending, it wound up, even after the book came out, was not the ending. Because then there was an epilogue, which ran in The New Yorker. So now my parents’ ashes are in a niche in a cemetery. A Jewish cemetery.

But because the story sort of existed, I think there wasn’t a framework for it, in a certain way. Which is different from other books where you don’t really know. There’s not a story arc. It’s just, like, I want to write about this.

INTERVIEWER

Did you think of the book as a graphic novel, or did you tell the story how you felt it needed to be told, and the subject gave rise to the form?

CHAST

I don’t feel like it was a “classic” graphic novel. I told it in the way it needed to be told. A mix of writing, comics, single panels, photos, cartoons that had been submitted to and rejected by The New Yorker, and the more realistic pen sketches at the end. I’m not good at conceiving of things in advance and then following that decision to the end of the line.

INTERVIEWER

You’re writing a book about dreams—which sounds tricky, like catching a moonbeam in a jar.

CHAST

There are so many really serious, well-researched dream books, but that’s not what I want to do. It’s not that. It’s a book about what dreams mean to me, and why I’m interested in them, and why I’ve always been interested in them, I mean, since I was a kid. The mystery of them, I guess.

I’ve been listening to The Interpretation of Dreams, because I realized I couldn’t proceed without at least knowing a little bit about what Freud said about dreams, and not just reading a Wikipedia article about it. But it’s weird, because I’m not an academic, and I’m not trained in psychiatry or psychology, so I feel like I need to put a disclaimer—“These are the opinions of not anybody who really knows anything about this.” After this I want to read Jung, because he had a whole different interpretation. And I have a couple of books that my son told me about that I loved, by a Jung scholar named Harry Wilmer.

INTERVIEWER

How do you revise your work?

CHAST

I read. I read it over. I read it. I read it over. Endlessly, endlessly, endlessly. And I make patches. That’s . . . If you saw the originals of any of the pages of my books, they have a lot of Wite-Out, a lot of patches.

INTERVIEWER

With editing, does a cartoon get more funny or get less?

CHAST

I think it gets better when you edit. I hope. I’m aiming for what I found compelling to write about, for that idea, to be as clear as possible. And if I want it to be funny, for it to be as funny as possible. And also to take as little time to communicate that idea and that humor as possible. With cartoons, there’s a lot of compression. I get pretty wordy. And I am afraid of being boring. So, I edit. I edit like crazy.

INTERVIEWER

But I don’t think of your stuff as sparse.

CHAST

No, it’s not. But it’s been edited a lot. I recently turned in a full-page thing—which they won’t take, I’m sure—it’s patch city.

INTERVIEWER

What if you need to revise something twice? Would you make two patches?

CHAST

I have patches that are, sure, a patch on top of a patch. It’s really 3-D. If it’s ever so slightly not in the same focus, nobody will notice. The idea is always what matters most to me.

INTERVIEWER

Can we talk about left-handedness? What does it mean to you to be left-handed?

CHAST

[laughs] What does it mean to you to be left-handed?

INTERVIEWER

It feels kind of like an identity to me. And I notice that a lot of people I admire are also left-handed—like you. It often corresponds to a weird brain. But then again, many righties are weird as well.

CHAST

That’s true. I do think that there’s something that’s unusual and maybe a little bit off about being left-handed. I have a few friends who are left-handed and I feel that we have certain things in common that are maybe hard to put into words. A slightly different way of processing information or something.

I’ve always been a lefty, since I was a kid. And drew from before I could write, as most kids do, but I guess I just didn’t stop.

INTERVIEWER

Do you remember learning to write?

CHAST

Yes. I do. I remember learning to write letters.

INTERVIEWER

Did your parents teach you?

CHAST

No. My mother said that I taught myself how to read. She used to read to me when I was little, and she said that when I was around four, I asked her to point out the word that said sometimes. And she pointed it out, and I was like, Oh, okay.

I was young for my grade, because I was born in the end of November—so when I started first grade, I guess I was five. And that was when most kids were learning how to read. But I already could read. And Dick, Jane, and Sally—that was, like, absurd. And this may actually have made things worse for me, because, God knows, I did not need another thing that made me stand out from other kids. But I was bored silly. My mother had a conference with the teacher, and after that the teacher would let me sit in the back of the classroom with a pile of paper and crayons and I would draw while the rest of the class was learning how to read.

INTERVIEWER

Were you a good student?

CHAST

I wasn’t a great student, but I was afraid to not get good grades, my parents being teachers. So I managed to keep everything above ninety. But I hated school. I had a couple of teachers who were wonderful, but mostly it was boring, and I didn’t know how to listen. I probably would be diagnosed with something these days.

INTERVIEWER

What did you like to read when you were a kid?

CHAST

When I was very young I read a lot of Beverly Cleary, Ramona the Pest. And I loved, of course, Harriet the Spy. I loved the Eloise books.

Comics were forbidden. My parents, who were schoolteachers, thought they were garbage and would rot your mind. They bought me Classic Comics, which were abominable. So I read about Archie and Veronica and Betty at the apartment of a girl who lived in my building. I didn’t love them, but at least they were more interesting than Classic Comics which were dense and boring and visually unpleasant.

I’m trying to think of who I liked when I was around eleven or twelve . . . I think that was when I was reading a lot of Mad magazine and stuff. I think when I was around thirteen, I got very pretentious and I started reading a lot of poetry. Allen Ginsberg. I thought of myself as sort of beatnik-ish. I don’t know . . . Alienated stuff. And then when I was around fourteen, I discovered Zap Comix, and all that underground R. Crumb stuff. I was mesmerized by them, even though I knew it wasn’t my world—I was a little young, and there was something repulsive about them. They seemed to be done by and for guys who called having sex balling, a word that is . . . Ugh. Still, I liked the “let’s just make stuff up” aspect.

INTERVIEWER

Were you reading comics all along, or did you take a break after being a kid?

CHAST

I read comics, I read lots of things. I liked stuff that was funny. I read National Lampoon—the comics in National Lampoon, the ones in the back. They had a whole section, I think it was called the Funny Pages, and they had tons of artists—Shary Flenniken, M. K. Brown. Do you know her stuff? She knocked me out. I adored her stuff, and still do. Ed Subitzky.

INTERVIEWER

What did you like about these comics? What about them did you learn from, as a cartoonist?

CHAST

I liked how idiosyncratic they were. There wasn’t just one style. People got to draw how they wanted to draw. And that the humor was not punch line, sitcom humor.

INTERVIEWER

And these were strip comics?

CHAST

Yeah, strip comics. Of course, Gahan Wilson did a whole strip cartoon for them called Nuts. It was sort of a takeoff of Peanuts, but it was wonderful, and it was all about being a child who was very fearful, very phobic, and I totally related to that.

Loved Mad magazine. I loved Don Martin. I loved the caricatures, although I knew it wasn’t something I was talented enough to do, or really that interested in. Mort Drucker, right? But they had all kinds of parodies that were great. They were the first magazine where I really saw American culture being made fun of. And it was weird. Maybe when I was in third grade I could watch stuff like Bewitched and love it, but as I got . . . eleven, twelve years old, I was already thinking, This is horrible and stupid.

I can remember being in seventh grade and by that point I know I’m not a regular kid here. I’m finding things funny that other people are not finding funny, and I don’t really understand how I’m supposed to be.

INTERVIEWER

Is that when you figured out that drawing was a good way to parody the world around you? Did the things you drew change at this point?

CHAST

Drawing was, and is, many things for me. Parody is a big part of it. Responding to things that I have no idea how otherwise to respond to. I’m no good at direct confrontation. I make a little note to myself—“Draw this up.”

INTERVIEWER

You’ve had various crafts practices over the years. Pysanka eggs, rugs, and lately, embroidery. You’ve shown them in galleries and had embroideries on the cover of The New Yorker—among the few nonillustrated covers The New Yorker has had. Do you think of these as a fine art practice?

CHAST

One good thing about going to RISD was that after four years of asking myself whether or not something was art, I didn’t seriously ever ask the question again. I approach the crafts as if I were painting. Just using thread, wool, pysanka dyes instead of paint. Idea, drawing, color and composition. Same stuff. Also, one thing about embroidery, if you saw how much picking out of embroidery and reembroidery was involved—the tiny scissors, the seam ripper, the tweezers—you’d barf. And one other thing, I don’t care what the back looks like. Some crafters are proud of neat backs. The backs of mine look like madness.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think there’s a hierarchy in art—like with fine art as more serious than cartoons? If not, does it annoy you that many people feel that way?

CHAST

Cartoonists and craftspeople—we sit at the children’s table. Don’t get me started about a lot of what people call fine art. So much of it is horrible, horrible art school bullshit. “Kriddlenap’s twenty- by eighty-foot canvas, with its multitudinous chromatic biomorphic forms, condenses the picture plane into a totality of architectonic textured cacophony. The sixteen basketballs that tentatively adhere to the surface are an ironic nod to . . . ” On and on. Fucking hate it. Endless pages of circle jerking.

INTERVIEWER

You told me you loved editing the 2016 Best American Comics, that you discovered new comics from editing it and it made you read differently.

CHAST

Yeah. I think I got way more curious about stuff. Until I did that book, I didn’t know the variety of comics and cartoons that were out there. I was living under a rock.

INTERVIEWER

When you like a comic . . . how do you know you like a comic?

CHAST

Me Tarzan. But seriously, when I want to keep reading it—that’s the main thing. When I did that collection, it was interesting once I had all the pieces sorted, because I felt they were very varied stylistically, and some of them were funny, some were quite serious, almost somber. There were black-and-white ones, there were color ones, there were ones that were very meticulously drawn, there were ones that were more loopy or casual. But there was something in all of them that kept me reading. I think they all felt sort of personal—not necessarily autobiographical, but I didn’t feel like the person was showing me how well they had mastered a certain genre. I felt like they were things that the person who created them really wanted to say, and really wanted to draw, and wanted to keep reading.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve collaborated on several books with Patty Marx, and you’re in a band with her. What’s the collaboration like?

CHAST

It is a lot of fun. My relationship with Patty goes back several decades. We actually first met through work, where we didn’t really know each other, but we were both starting our careers. She did a humor piece for The Atlantic Monthly and they asked me to illustrate it. Her mother said to her: I liked your piece, but I really liked the illustration, and you should call that girl up. So Patty called me up. It’s the only time that has ever happened—that somebody I’ve done a piece for has called me up and said that they liked it.

The other thing about collaborating with Patty that I really like is that it’s not like she hands me a manuscript that’s done, and then I do the drawings. There’s a lot of overlap. It’s a little bit Venn diagram–y, there’s an area in the middle where she can give me suggestions for drawings and I can give her suggestions for ideas. This ukulele thing is another kind of collaboration, which is really fun. She’s so funny, and she’s great at lyrics, and I can figure out the chords, and . . . Basically, it started because we wanted to make each other laugh. And, so, I think we’re continuing to do that, just trying to have fun—and it’s not serious, it’s . . . Patty has quoted a doctor, saying, It’s like a vaccination—it’ll be over in a second.

INTERVIEWER

Speaking of seconds—we have a very uncertain profession. We’ll be on top of the world one month, and then the next month afraid we’ll never sell a cartoon again. Does that affect how funny you are able to be? And how do you work through that?

CHAST

I have tried different tactics. The only constant is that when I sell a cartoon, I feel great. When I don’t sell a cartoon, I feel like shit.

INTERVIEWER

For readers unfamiliar with The New Yorker’s process, each week cartoonists submit a batch of sketches—the usual number is ten. The comics editor, now Emma Allen, and what they call the A-issue editor choose a few from each batch, then, later in the week, the magazine’s editor in chief, now David Remnick, will look and they’ll choose maybe twenty cartoons in total. Then fact-checkers make sure the chosen cartoons aren’t too close to anything that’s already been published. Cartoonists are notified on Friday if one of their cartoons has made it through this gauntlet.

Do you have a number of cartoons that you make yourself make each week?

CHAST

Yes.

INTERVIEWER

Do you want to publicize it?

CHAST

Sure. It has to be at least six. It might be eight on occasion. I mean, I might submit eight, but I can get six cartoons that I can submit. I mean, I will generate more than that. But six doesn’t seem too low. And too many, that worries me on the . . . Because then I think, there’s so many people submitting cartoons, why would I want to burden them with more than . . . I don’t think it has anything to do with anything. Because, as you said, our profession is, as Lynda Barry once said, “very rickety,” which I think is a perfect word for it. So we make up all of these kind of . . . the lucky number.

And sometimes, you can also get to this point where it’s like, well, I’m not going to sell anyway, so I’ll do what I want to do. Like recently, I wound up taking a screenshot of this funny list of searches about inflatable hot tubs. I mean the whole idea of an inflatable hot tub just cracked me up. Where do you put it? Do I put it in my apartment? A kid’s wading pool is already risky enough. But I could see having, like, a tiled . . .

INTERVIEWER

It’s like hot water . . . [both laugh]

CHAST

Right, and it’s boiling away! And you have it in your apartment? And the wiring! I’ve already had enough paranoia with a regular tub falling through the floor, that, I don’t know . . . It cracks me up, the idea that anybody would get this. And the pictures, even, with this inflatable hot tub. Plus, plus, there’s a giant electrical motor sort of perched on the side next to all this water. And then there’s these four people inside of it. I’m like, This is nuts! This is the most insane thing I ever saw.

So, who knows if they’ll take it or not. I hope they do. But that’s an accidental thing—I was not googling inflatable hot tubs. It just popped up, and then it happened to make me laugh. And I followed that thread. And that is my favorite thing. When something accidentally happens. It’s very hard for me to set it up so the funny thing pops into my path. But if something does pop into my path, I’m very happy I can say, Okay, that’s what I’m going to do. That’s the cartoon.